|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

On a debut album, many artists play it a little “safe.” Show your capability but save your boundary-pushing for a follow-up. Anna Butterss did not seem to get the memo. Activities (Colorfield, 2022) finds her expanding her scope well beyond not only the music for which her current fans may know her but also her usual instrument.

That is not to say that those familiar with Butterss’ work to date would not find something to draw them into the album. Butterss is probably best known in some circles for her role in supporting singer-songwriters, including Phoebe Bridgers, Aimee Mann, and Christian Lee Hutson. The beautiful musical simplicity from such experiences echoes on tracks like “Limitations and Dogma,” where sparse keyboards and skittering drums gradually build into a mid-tempo shuffle.

Others are possibly more accustomed to Butterss’ bass work on Makaya McCraven’s Universal Beings (International Anthem, 2018) or Josh Johnson’s Freedom Exercise (Northern Spy, 2020). On both, studio mastery created new sounds by manipulating a combination of improvisational creativity. This aesthetic is also present on Activities. With the opener, “Entrance,” a steady bass groove and a repeated faint harp-like synthesizer give way for a mysterious-sounding flute, further obfuscated by additional synthesizers.

While connections to Butterss’ previous works are present on the record, Activities largely stands out on its own. Part of this comes from the unique environment in which it was born. The recording itself was never intended for release. What started as an opportunity for Butterss to go into the studio and “mess around” for a day somehow turned into Butterss recording on several instruments. Including all of the parts mentioned above. Of the dozen tools at her disposal, most she had never played before. Others, specifically the flute, she long abandoned. Interestingly, you can neither tell from the sound itself that she lacks significant experience with several of the instruments. Or even that it is one person playing most of the parts. This is perhaps most evident in the album’s use of synthesizers. Butterss’ adds their colors carefully, as if a painter seeking the perfect stroke. On a song like “Super Lucrative,” the synths are all-encompassing and have an imposing presence. By contrast, with “Do Not Disturb,” the synths subtly, almost imperceptibly, weave along a frenetic upright bass line. At other times there is a very heavy 80s synth-pop vibe to the album, but it never seems dated.

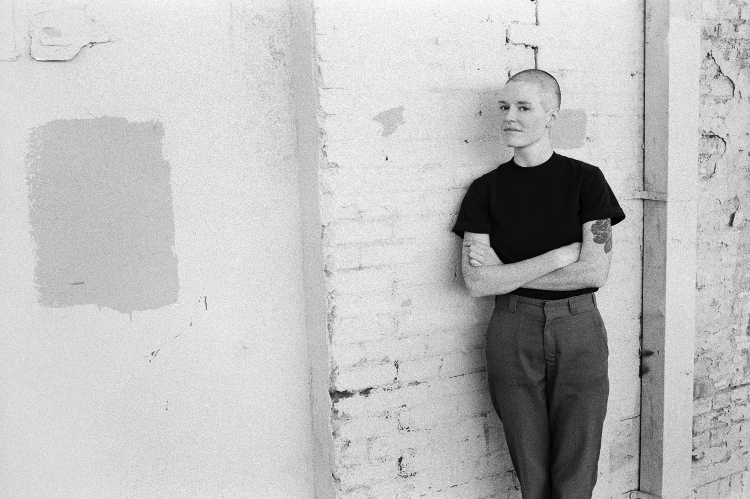

We sat down with Butterss to discuss her bold debut and some of the instruments in her arsenal. We also cover her time in her home city of Adelaide, Australia, and her adopted home of Los Angeles.

PostGenre: Let’s go back to the beginning. When did you start playing bass, and what got you into the instrument?

Anna Butterss: Oh, man. I started playing bass when I was 15. I started on the upright. Funnily enough, at the time, I was going to a music high school, and my primary instrument was the flute. But I was starting to get a little bored with the flute and felt like I was a little disconnected from it. My music teacher suggested that maybe I consider playing another instrument.

PG: And that led to the bass?

AB: Well, at first, I started to panic a little bit. I knew I wanted something different from the flute but was unsure what instrument would speak to me. Around that time, I also started listening to jazz. Before that, I had not listened to much jazz music. I liked how improvisation, being such a huge part of jazz music, gave the artist more creative freedom. My high school had a great jazz program and I wanted to be a part of it. So, I decided to try an instrument that I could play in their jazz groups. From the very first time I played the bass, it just felt so natural to me; more than the flute ever did. The bass allowed me to express myself better than I ever could on the flute.

PG: But you also play flute on Activities.

AB: [laughing]. Yes. Playing the flute on the album was not something I intended to do when [co-producer and mixer] Pete [Min] called me and asked if I wanted to make a record. Because his concept with the Colorfield Records label is to have artists play instruments they are less familiar with, he started asking me if I play guitar, drums, or piano. I don’t play any of those instruments.

PG: Though, Activities finds you performing on all three.

AB: Right. I think I can get them to make the sounds I was looking for on the album, but they are not something I play at a professional level, not really anyway. But as far as the flute, after I told Pete that I couldn’t play the instruments he named, I suggested that I could do something on the flute. Though I never intended to play flute on the album, it was nice to reconnect with that instrument that I once loved and later grew tired of; to play it without negative emotions.

PG: What excited you the most about the challenge of playing instruments with which you are less comfortable?

AB: It was the freedom behind the idea. Pete gave me a lot of space to experiment. We didn’t have a timeline or a deadline, and I was excited to try new things. The album also heavily relied upon the editing process to compose the tracks, which gave me more opportunities to make things sound as I wanted.

PG: Speaking to that editing aspect of the album, you have worked previously with Jeff Parker…

AB: Quite a bit. For the last five or six years, we have played together at a bar in Highland Park on Monday nights with Josh Johnson and Jay Bellerose. Jeff is a huge influence on me and a good friend. I’ve learned a lot about improvising about creating music from Jeff. And even when I am playing guitar on the album, it is very heavily influenced by Jeff.

PG: At certain times, due to your piecing parts together of different recordings to make songs, Activities has an aesthetic similar to that one can find on Parker’s New Breed albums. Or as Makaya McCraven does in much of his music. Do you feel your work with Pete on this album fits alongside those other projects?

AB: Definitely. 100%.

As far as Makaya, I have been a fan of his since In the Moment (International Anthem, 2015). I listened to that album a lot when it first came out. It was my first experience listening to music that mixed acoustic improvisation with electronics and cutting up recordings to add layers. Of course, playing with Jeff also allowed me to get into that kind of music. I was also really into New Breed (International Anthem, 2016). Both Jeff and Makaya are good friends of mine and big influences. It was an ambition of mine to follow their influences on this album. So, I’m happy that you’ve made that connection.

PG: Do you see putting together songs in that way – taking excerpts of different recordings and mixing them- as an extension of improvisation?

AB: I do. The way that we pieced the album together involved a lot of experimentation and seeing where things fit best. It was like improvisation, in the sense that you are experimenting until you find something that sounds good. Although production is not in real-time, I do see them as the same; an extension of the same palette.

PG: So, how much of the pieces on Activities are improvised, and how much are through-composed? It is a little difficult to tell at times.

AB: Great, I love that it is not obvious.

When I went into the studio to make the album, I didn’t plan to do anything too ambitious or specific. I wanted to let my mind run free and see what came of it. I was also not expecting some of the feelings that came out in the process.

The first few songs on the album we made as we went along. I came in with no ideas. I just chose an instrument and played something. The next day I would start on another instrument. And on the third day, yet another. We layered the parts together and saw what would make them fit. About half of the record was made that way. The rest were songs I brought into the studio. Each of those pieces was in various stages of completion. A few, “Blevins” is one, I had started working on during the [Coronavirus pandemic] lockdown and had not done much with yet. And some others I brought in, I had written years ago and reworked in the studio.

PG: In terms of the feelings you referenced, they include those you had about being away from your home city of Adelaide, Australia, for a decade.

AB: Right.

PG: Do you feel there is anything specific that you could point to on Activities that came from the music of Adelaide?

AB: Oh, that’s a good question. I feel like growing up in Adelaide was a bit double-edged in terms of music. From age 14 onward, I couldn’t wait to leave and go to America just because there were not many musical opportunities in Adelaide. The city is a bit removed from not only the rest of the world but also other cities in Australia. It is about an 8-hour drive from Melbourne. Adelaide is ultimately pretty isolated, and your musical opportunities are somewhat limited there.

But, at the same time, Adelaide has a very cool, weird, creative music scene. No one outside the city seems to know about it, but that scene has some great musicians. I started exploring that scene when I was about 15, and my dad took me to various concerts. People were doing crazy stuff and making very special music. Most of those people are still there. Although it wasn’t my path, I have so much respect and admiration for the people who stayed there their whole lives and keep making this very cool, weird music.

Of the songs on Activities, “The Worst Thing You Could Do For Your Health” is probably the one most reflective of the scene in Adelaide. On that song, I went very far out. It has gritty energy that is unlike anything else I tend to write, and I feel that it comes from some of the bands I watched growing up.

PG: Why do you think the scene is not well known outside of Adelaide?

AB: I think it is, unfortunately, due to Adelaide’s geographic location. More people know about the scenes in Melbourne or Sydney partly because they are larger and less remote cities. Also, a lot of people leave Adelaide and move to places like Melbourne or the [United] States. So, Adelaide’s creative music scene is essentially hyper-local. There is a studio and label down there called Wizard Tone that makes some very cool records. But the scene is still a very contained thing; it seems very limited to the local community.

PG: After moving to the United States, you spent most of your time in Los Angeles. Why LA compared to New York or Chicago?

AB: That is like the age-old question, isn’t it? I did live in Indiana for two years before moving to LA. I was in Indiana for graduate school and, after I graduated, I had to choose between Chicago, New York, or LA because those seemed to be the best cities to live in if I was going to start a career in music. I always had my sights set on Chicago because I have a lot of friends there. And, of course, the creative music scene in Chicago is incredible. But I ended up moving out to LA because my partner was living here. We planned on giving LA a try and, if it didn’t work out, we would move to New York. But around that time, in 2014, many other musicians started to move out to LA, including Jeff Parker. And that made it easier to stay here. More and more younger musicians keep moving here, as well. The creative music scene here keeps improving. I’ve never lived in New York, but I have heard from others that it is easy to get pigeonholed there musically. In LA, you can do many different things musically. I find that both invigorating and stimulating.

PG: In terms of not being pigeonholed, you have also worked extensively with several singer-songwriters, including Phoebe Bridgers, Aimee Mann, and Jenny Lewis. Do you feel your experience with singer-songwriters influences your compositions or improvisation?

AB: My work with singer-songwriters has had a lot of influence on my compositions. For one thing, working with the musicians makes me play a lot more electric bass. Without those projects, I wouldn’t play much electric. Playing a different instrument makes you approach music differently, even when back on the upright.

But I think the biggest thing is that those experiences taught me how to think on a larger scale. Instead of focusing primarily on technical aspects like chord changes, it helped me think more globally about my role in the song.

PG: Those experiences have given you a broader view of the music.

AB: Exactly. A more macro perspective of the music. That perspective has helped me find ways to create bass lines that would fit into many different types of music. There is also the simplicity of singer-songwriter music. That is not to minimize that kind of music, just to note that sometimes jazz overcomplicates things out of habit. Working with singer-songwriters teaches you how to focus on the real essence of the music and what the music needs from me at that exact moment.

PG: Did that that macro approach help you when putting together Activities?

AB: Yeah. Or, at least, I think so. When I was piecing the album together, I thought about the mood I wanted for each song. I focused a lot more on the emotion I was hoping to express and less on specific ideas of musical theory. That comes straight from this more high-level view of music.

PG: You also sing on the album. You previously indicated that sometimes you find it difficult to express yourself with language. Did that difficulty make you more hesitant to sing than play an instrument?

AB: Yeah, definitely. I have sung backup on a few tours that I’ve been part of for other musicians. I have always enjoyed it. I also grew up singing in choirs for several years. I enjoy singing, but I also know so many great lyricists – including Aimee, Phoebe, and Jenny- on a personal level. It is very intimidating knowing what those people can do with their voices compared to me.

I think Pete pushed me to sing. It’s not something I am entirely comfortable with recording, but I have been trying to improve my vocal skills and felt comfortable with putting some “oohs” and “ahhs” on the album.

PG: You may also be stepping outside your comfort zone with the synthesizers used throughout the album.

AB: The synthesizers were another thing that Pete pushed me to play on the album because I hadn’t played them before. I found myself gravitating towards that combination of acoustic instruments and synthesizers on many songs.

PG: Do you see much difference between electronic and acoustic instruments?

AB: That’s an interesting question. I don’t know if I would see electronic instruments as categorically different from acoustic ones. They are ultimately all instruments; all opportunities to create sound. Which to use when and how depends on your vision for the song.

PG: Are synthesizers something you would like to explore using further?

AB: Definitely. We also messed around with drum machines a little for the album. I’ve also never really used drum machines before. Between choir, orchestras, and jazz school, I have a background that heavily emphasizes acoustic music. But I think I will continue to explore that space between acoustic instruments and electronic ones and see what interesting music comes from it.

Activities will be released on Colorfield Records on July 8, 2022. It can be purchased on Bandcamp.

More information on Anna Butterss can be found on her website.

Leave a Reply