|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

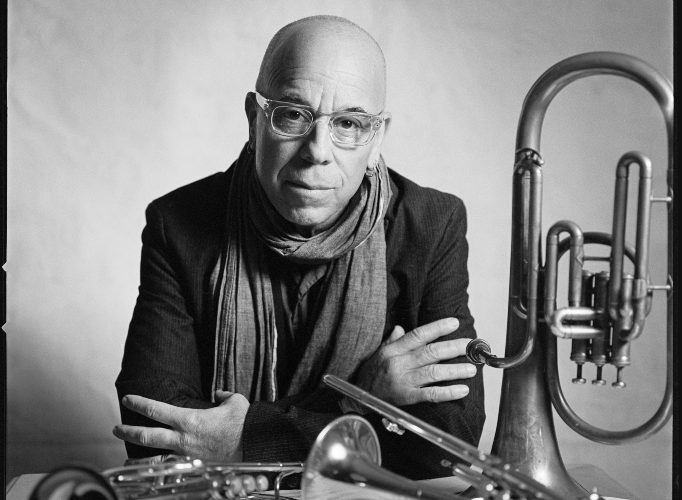

Since arriving in New York over forty years ago, Steven Bernstein has established himself as a powerful voice in music. One commonality across most of his work has been a consistent refusal to be boxed into a particular style or approach. Many may point to his relationship to the downtown music scene. In 1990, the trumpeter joined John Lurie’s iconic band, The Lounge Lizards, in its melding of jazz, rock, pop, and experimental music. Bernstein also worked with Bill Frisell, Bill Laswell, Laurie Anderson, and Lou Reed. He collaborated with the late Hal Willner on several different projects over three decades and has released four albums for John Zorn’s Radical Jewish Culture series. Part of the entry into that community comes from Bernstein’s immense skill as an arranger. A review of his arrangements also shows that the diversity of his artistry extends beyond these avant-garde influences. Ben E King, Elton John, Roger Waters, Jim James, Levon Helm, Woody Allen, and Lee “Scratch” Perry are among those who have called upon his expertise. And, of course, there are Bernstein’s arrangements for his own bands. With Butler, Bernstein & The Hot 9, he joined New Orleans piano master Henry Butler in breathing new life into songs by artists like King Oliver and Professor Longhair. Over the last quarter-century, his quartet Sexmob has obtained notoriety in part due to its fearlessness in covering the music of everyone from Duke Ellington to Prince to Nino Rota, each with an incomparable sonic twist. With The Millennial Territory Orchestra (MTO)- Bernstein’s take on big bands- he joins musicians he’s known for most if his career in visiting the compositions of the Beatles and Sly and the Family Stone, among others. We sat down with Bernstein to discuss his most recent project, Community Music, a four-part series scheduled for release on Royal Potato Family Records over the next year. Volume one, Tinctures in Time (Royal Potato Family, 2021), is MTO’s first album of entirely original compositions. Like much of his works, the songs are difficult to categorize, more focused on communicating with the listener than hastily applying labels.

PostGenre: Tinctures in Time is a pretty incredible album, what…

Steven Bernstein: You know, I’ve got to say something. This is the first interview I’ve done for the album. It means so much to me to hear you say that about it. When I made the album, I played it for Hal [Willner] and told him that I didn’t even know what to call this kind of music. Hal simply responded that “it’s Bernstein music.” That made me question whether it would mean anything to people listening to it. I mean, can I ask you a question before you ask me anything?

PG: Sure.

SB: What is this music?

PG: Well, it is hard to label. There is certainly a “jazz” element to it, but many other things are going on as well. It is an incredible recording. There is one song in particular, “Angels,” that is incredibly gorgeous.

SB: After playing with Levon [Helm] for so long and being immersed in his music, there’s some of that influence in there as well. There are so many different kinds of music pulled into it. The music is so real and honest. I feel like it best represents where I am at this point in my life.

As far as the “jazz” element, am I a “jazz” musician? I don’t know. Some people might say I am. Years ago, Hal and I worked on the movie Kansas City (Fineline, 1996), which depicts the Midwest jazz scene of the 1930s. When we first started on the project, I was a little nervous. I told Hal that I wasn’t sure I could connect with the film because I wasn’t a “jazz” musician. At the time, he told me that of course, I was one. But, years later he came back to me and shared that he could understand why I didn’t identify as a jazz musician. Even though I love “jazz” and it’s probably the biggest part of my musical DNA, I’m not someone who focuses almost exclusively on “jazz.”

PG: You’re not a “purist.”

SB: Exactly. Marc Ribot has a great line, “here’s the first lesson in arranging: jazz- tenor sax. Rock- electric guitar. Classical – violin.” In a sense, when you play the trumpet, there is an assumption you play jazz music because of artists like Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis who came before on the instrument. But it has sometimes confused people that I don’t fit perfectly in line.

Instead, I play music that is very personal to me but may not fit what others may expect. Sometimes that makes things a little difficult for my role as a bandleader because there is usually some pressure to identify your music. But it’s always been natural to me to take a broad view of music; why not use every element you love?

PG: Where do you think that sort of eclecticism in sound comes from?

SB: Honestly, I think it comes from how I was raised. I grew up in Berkeley, California. When I was eight years old, I went to a Black Panther Summer Camp, a summer program for kids that the Panthers ran in Oakland. I had friends with gay parents as early long as I could remember. I went to integrated schools. I mention all of that to say that I grew up in a world where the idea of boundaries- old social ideas that a certain person or idea should be confined to limited areas – were being broken down for me at a very early age. I’ve always seen the removal of barriers as a natural thing. I came up with the idea of trying to absorb everything in the world instead of just what certain segments of society may say was intended for someone “like you,” in whatever way you even define that phrase.

A lot of people ask me how I started playing the trumpet. I usually answer that in the 4th grade, they showed us a slideshow of instruments at school and had us pick one. I liked Louis Armstrong and thought he was cool when I saw him on TV. I have often said that I probably picked the trumpet because of my admiration for Armstrong. But I’ve told that story so many times that it got to the point where I couldn’t tell if it was the truth or just something I convinced myself over the years to be true. But, years later as my parents were moving out of their house, they found an old scrapbook from around ‘72. I was only 11 years old at the time but, apparently, when Louis Armstrong died, I had cut out every single article about his funeral and put it into the book. I even bought a Life magazine, we didn’t have it in our house, just so I could get all of the magazine’s photos from his funeral.

In ‘79, I moved to New York. Suddenly I saw that people making free jazz or punk were also getting together to make funk music in the East Village. It was a huge revelation for me. I still thought that maybe there was some division in types of music. I loved the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Louis Armstrong, and P-Funk, but somehow, in my mind, those were segmented. But when I saw people mixing all that stuff together, there was no reason for me not to do the same thing with my music.

PG: New York. The late 1970s. Mixing different sounds. Around the same time, in the same city, DJs were beginning to piece together ideas using turntables. And then later, in the 90s, you did some work in the jazz/hip-hop hybrid sphere on Digable Planets’ Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space) (Pendulum/Elektra, 1993) and DJ Logic’s Project Logic (Ropeadope, 1999). Do you feel like the rise of sampling shaped your approach at all?

SB: Oh, absolutely. Some of my friends and I were among the first white people to hear hip hop. It was breaking in downtown New York way before it was on the radio airwaves. We were listening to people like Afrika Bambaataa spinning at Danceteria. And when the first Public Enemy record came out in, I believe, the summer of ‘82 with all of those crazy samples, it was huge. De La Soul was as well.

In the mid-‘80s, some of the first studio recordings my friends and I did were for remixers. Some of the big guys at the time – Little Louie Vega, Frankie Knuckles, and others – came to us and asked if we could freestyle over a track. The DJs would always pick the weirdest things from those sessions and make loops out of those strange moments and build a track around the loops. The idea of incorporating loops and samples very much became a part of our vernacular.

PG: But you also do not use samples in your music.

SB: Right. Don’t get me wrong, while the influence is there, I am certainly not a hip-hop expert. I’m not like some of the younger musicians today who make samples and modern technology a central part of their music. I feel like I am really out of step with that approach; like I am the last guy who just goes into the studio and records things.

And you see that – musicians in the studio playing and reacting to each other- on these new Community Music albums. We’re not doing all the things that people do now where you use technology like Pro Tools on a grid. A lot of times now if people see that, say, a drum hit is off the grid they just move it. They don’t even listen to see what it sounds like; they just look at it and move it. But I feel like that approach often takes away from the music. The first time we were recording these four albums, the engineer tried to move something on the grid and I told him that if he was going to move it, he would have to move everyone’s reaction to what happened as well. I come from an era where it’s all about reactions. In a sense, this new approach of basic music on the grid overlooks real human reactions to one another.

PG: As to the importance of person-to-person interaction, you have played with the members of the Millennial Territory Orchestra in various configurations for a long time.

SB: Yeah! I’ve known [saxophonist] Peter Apfelbaum for close to 50 years at this point.

PG: When you were writing pieces for the new albums, did you focus on the instrument or the specific musician in writing a set part?

SB: Oh, always the musician. Everything I write is based on the musicians who will be playing the parts. If you go into my original parts, they don’t even have the name of the instruments. Instead, they show the names of the musicians playing each part. That approach comes from the Duke Ellington school of writing where everything is written for a specific human being. When I write a note, I know what that note is going to sound like. If, for instance, I want a particularly strong accent on a note, that desire will guide to whom I assign that particular note. Or, if I need a note to be inside a chord, I may be more likely to give it to someone else who would be less likely to blast the note out. [laughing].

PG: In general, it seems you have focused more the last few years on original compositions than arrangements. Tinctures in Time is the first album for the Millennial Territory Orchestra without other writers’ compositions. The most recent album for Sexmob, Cultural Capital (Rex, 2017), also consisted entirely of originals. Where did the increased focus on your own writings come from?

SB: I don’t know if focusing on my own writings was something I intentionally set out to do. But I think, in a sense, part of it is that everything I do is original. Arranging is such a misunderstood and badly compensated profession. Arrangers create all of this original material around a hit song. A lot of times the thing you remember most might be the hook that the arranger wrote, not always the most important part of the underlying song. Even when I am arranging, I am always writing music. Once I realized that I am writing either way, though I love arranging, I started wondering why I didn’t just write from scratch.

There is a certain safe starting point when you are an arranger. You already know you are working with a great song. And when you’re someone like me who focuses on performing for audiences, arranging provides an additional safe spot in that it centers listeners. You might be going off into some zone that your listeners might not always be familiar with, but then if you go to some familiar melody, they get hooked again. The performer has that great moment where you give the audience something that really touches them because they hear that song that they love.

In a sense, it is a real leap of faith to say, “OK, here’s my music. Are you going to feel the same way?” But I feel like it is just part of the process. Original compositions are a natural place for me to go just because there are always little things I’ve written down on pieces of paper. The work comes in putting them into a form and creating a composition out of them,

PG: How do you feel your significant time arranging has influenced you as a composer compared to if you started with all originals?

SB: Well, over the years arranging has given me a lot of language. When you work on thousands of arrangements, as I have, it makes you understand how other composers – whether Ellington or Mingus or Leonard Cohen- make their music work. And that extends to how people like Prince, the Grateful Dead, or the Beatles put particular songs together. That understanding of what makes their songs work gives you all this language you can use. It gives you more opportunities and pathways for writing your own compositions.

PG: So, just to pull from one person, what did you learn the most from working with Henry Butler?

SB: Wow, that’s a heavy question.

You know, I learned a lot about harmony from Henry. Unlike many musicians, I don’t play the piano in any serious way. Obviously, I can use the piano to see a chord and that sort of thing. But I don’t have technique on the piano. Most of the stuff I write is in my head and then, because I don’t have perfect pitch, I will go over to the piano and confirm that some of the notes in my head are what I think I am hearing. But when I would write music for Henry, I had to figure out something specific on the piano beyond just normal compositional ideas. There is a certain kind of pianistic harmony, especially with that New Orleans music, that I had to buckle down with and go “what is this?” And then I would hear it, learn it, and make it part of my language too.

But another important thing about Henry – and the reason we were kindred spirits – is that he shared my belief about our jobs as musicians. Our job is not to play great music. While you do aim to make great music, ultimately a musician’s job is to transform an audience. I have never cared what people think about my notes or my specific technique or anything like that. Instead, what is important to me is that the audience feels something. Henry felt the same way.

Shortly after Charlie Haden’s death, his family and friends put on a memorial concert to remember Charlie. I was out of town at the time but after the memorial, Roswell Rudd called me and said, “Little Slide” – he always called me “Little Slide”- “you know, there were a lot of fine musicians that played that day. Everyone there was a fantastic musician. But your friend, Henry Butler, changed the molecules in the room.” And that is our job as musicians; to change the molecules in the room. Anyone can play great music. You just practice over and over again and eventually, you get good. But that other stuff? That’s why we’re doing this. When I performed with Levon, that was what we attempted to do as well. The same with Sexmob and, really, all of my bands. I am playing for the audience, not myself. I am not making this music to show you what I can do. I am playing for you. And Henry solidified my belief in that perspective. Henry was one of the greatest musicians ever. He could play anything he could hear, or not here, and there will never be another like him. And, for a guy that brilliant to focus entirely on making sure the audience feels something, that’s incredibly powerful.

Click here for part two of our conversation with Steven.

The Millennial Territory Orchestra’s Tinctures in Time (Community Music, Vol. 1) will be released on September 3, 2021, on Royal Potato Family. More information can be found on the label’s site or on Steven’s Bandcamp.

More information on Steven can be found on his website.

Leave a Reply