|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

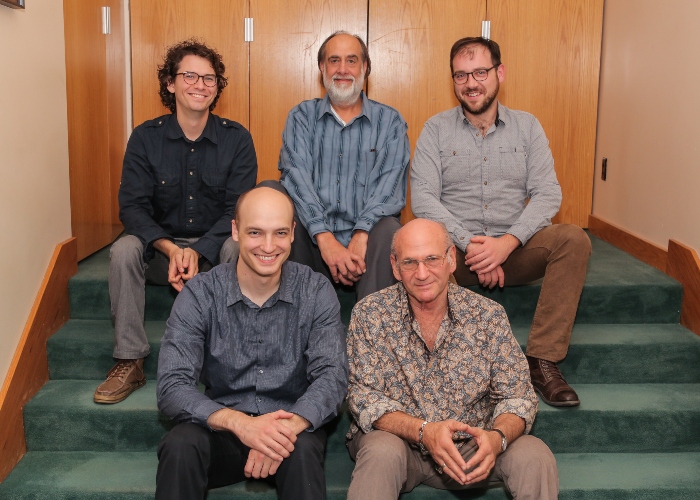

The second part of our conversation with Dave Liebman covers his incredible debut as a leader, Lookout Farm (ECM, 1973). But it focuses primarily on two of the saxophonist’s more recent projects. First, we discuss his longtime collaboration with pianist Richie Beirach and their recent five CD release – with special guest Jack Dejohnette– Empathy (Delta Music, 2021). We conclude with a lengthy discussion on the influence of another saxophone great, John Coltrane: Liebman’s time as a teenager witnessing the raw power and beauty of the legend’s music firsthand at Birdland, his time with Elvin Jones, and his stunning new recording with his Expansions quintet, Selflessness (Dot Time, 2021). Read the first part here.

PostGenre: After your time with Miles, you recorded Lookout Farm. It is overlooked in some circles but is really an incredible album.

Dave Liebman: Thank you.

PG: One really fascinating thing about it is that in addition to jazz, the album pulls from music from different cultures around the world. The guitar sounds maybe a little Spanish. Then you have Badal Roy on tablas. Over the past two decades or so, there has been an increased emphasis on melding influences around the world into music coming from the jazz tradition. Do you feel like Lookout Farm was in some ways ahead of its time in this sense?

DL: I don’t know about it being ahead of its time but it was definitely on time. We did have the tablas and on one recording, Sweet Hands (Horizon, 1975), we went full into those Indian influences by adding ektar, tamboura, and sitar.

On Lookout Farm, the idea was that each of the four tunes had a different kind of vibe, with each representing an interest of mine at the time. Lookout Farm was in tune to the times. You had acoustic bass and electric bass. You had electric piano and acoustic piano. Drums and tablas. It was a great period and the music represents our influences being shaped into a band.

The four tunes on Lookout Farm are the same things I’ve been playing throughout my life. I’m incredibly proud to have that album as my first as a leader. I often tell younger musicians to be very careful with their first recording and think about the implications of releasing it. Your first record will always be something you are judged for. Last week I received a royalty statement that after almost forty years the album has sold 25,000 copies. That was a necessary stage in my career.

One night in Brazil with Miles I told him I was leaving him to form my own band. He asked me why and I told him I had the guys and the music I wanted to play well-rehearsed. “Are you going to play that corny shit of eight-bar cycles?” [laughing]. And I said, “look man, you did it for forty years.” [laughing]. Again, he was funny. Only a few words at a time, but a funny guy.

But the core of the fusion thing is Weather Report. When Joe [Zawinul] and Wayne [Shorter] went out to form the group, they ended up making music that was really the band of that era. They reflected pop, rock, and world music. Even Cannonball Adderley’s influence is in there because of his work with Zawinul. In a way, Weather Report was the band that represented this whole ten-year period of the 1970s.

PG: One of the members of the Lookout Farm was Richie Beirach. You have worked with Richie on several different projects over the decades. What do you think it is in his musical ideas that resonate so well with yours and vice versa?

DL: Well, socially we have a good time. We actually came from the same neighborhood. We didn’t know each other growing up because there’s so many people in Brooklyn. But the roots of who we are were pretty much spelled out musically and socially by the late 1960s. He was a guy I could talk to who offered his extensive knowledge concerning 20th Century harmony, which I was interested in. That’s what separates us from many other duos. After all, we could “jam” on Bartok!!

Our relationship was really based on eclectic influences. When people ask me about the music of the 1970s or 1960s, I always offer them eclectic as the one word to best describe the times. Before the 1970s, that jumping around in styles didn’t really exist. Jazz was based on the blues and rhythm changes but it had really a limited repertoire that was molded by different people like Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers and Horace Silver. By the 1960s, this repertoire was mostly gone even though people still play it today. Instead, the music had melded into other things that were going on musically. Musicians had to find a way to instill this vibe of the repertoire into what was happening contemporaneously. Even now, Richie and I keep working together. We just put out a five-CD set [Empathy] of completely free playing with Jack DeJohnette on one of the CDs. Richie and I still talk to each other pretty much every day.

PG: On the topic of new recordings, one of your most recent releases was Selflessness (Dot Time, 2021) where your Expansions quintet visited the music of John Coltrane. You have long mentioned your admiration of Coltrane’s music from the time you saw him perform at Birdland in 1962. One thing we had jumped over in going from Ten Wheel Drive to Miles was your time with Elvin Jones. Was it surreal to be the saxophonist in the band of the guy who had made such great recordings with your hero?

DL: Oh yeah. Oh god yes. I pinched myself a lot. To go from listening to Elvin and Coltrane to being in Elvin’s band was incredible. Obviously, it made me feel very good. I had accomplished something that most of my peers didn’t. But at the same time, it was incredibly nerve-wracking. I kept thinking about it in terms of the dynamic between Coltrane and Elvin. So Jeff Williams and I would play a 20-minute duet to fulfill the Coltrane legacy. Of course, you can’t do that. Every band is different and Elvin wasn’t going to go back and play the way he had played for Coltrane with Dave Liebman or Steve Grossman!! That would be blasphemous. Elvin didn’t think of it that way though, he just played. Being in those shoes was definitely heavy.

One thing Elvin does that is emblematic is how he plays behind the beat on the ride cymbal. No one does it better than him and I had to learn it. Nothing is on paper. It has to do with the pulse and lining up of beats. Dexter Gordon is one of the chiefs of this way to play. But Elvin, as the drummer, made sure that we had to be on the case or you are going to sound wrong. That took me about four to six months to get used to. But from then on, I could play behind the beat with no problem. Very small mountain to climb but very important to do.

Elvin was a very pleasant person. He had been through a lot, no question about it. He was trying to get off of medication at the time. Once in a while, he would drink a little bit more than he should and start acting a little strange, but that was forgotten by the morning. [Laughing]. I loved Elvin. I love his presence, his vibe, and of course his playing. He represented a very warm, inclusive and non-regimented way of being. There was an honesty in his playing…..something really true and real when he would sit down at the drums. I put Elvin right up there with my father in terms of respect.

PG: Do you feel like the things that first drew you to Coltrane’s music and what fascinated you about him when you were 15 years old are the same things that interest you in his music now or have you found more depth in the music as you have continued to listen to it over time?

DL: Definitely more depth. Coltrane covered basically everything in the span of only ten years. Well, twelve years officially. From ‘55 to ‘65. And by ‘67 he was not playing much. He had it covered. But the more you listen, the deeper and deeper you find yourself in his music. Like anything else that you enjoy, that quality will continue to open up like a rose. If you can nourish it and let it be, it can really grow.

PG: You have made several excellent Coltrane albums over the years. What do you feel sets Selflessness apart from those?

DL: I didn’t do any of Coltrane’s music in any significant way in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and into the ‘80s. I refused to do it because I didn’t want to get caught up in people trying to compare my sound to Coltrane’s … which of course ended up happening anyway. By the mid-80s, a French label approached me with the idea of doing a Coltrane album and I decided to go for it. That one was Homage to John Coltrane (Owl, 1987) and is half electric, half acoustic.

I decided that if I was going to do Coltrane’s music, I was going to adapt it to my way of playing. And that adaptation is what has guided the six or seven records I’ve done of Coltrane’s music. Not everything is starkly different but they were different enough that every time I was working on one, I was using arrangements that were different from what anyone else was doing.

With Selflessness, I get to perform with my new band. We’ve been together for about five years now and these guys play differently, especially the piano player Bobby Avey. They have a different way of listening, just as we did when my generation came on the scene with the older guys like Elvin or Miles. You could almost make a case … (I should do it someday)… that every ten years jazz significantly changes. I go back and compare some basic solos over a song like “All the Things You Are” to a decade later when people were playing free. You are going to hear a whole different thing from musicians who are in their prime right now and represent a whole different era. So I decided to take advantage of the younger guys and their approaches, just throw the music out there and see what we could do.

I’m seventy-five years old. Who knows how much longer I have. I feel like Selflessness could be the last Coltrane album I do and then finally put it to sleep.

PG: As you point out, Expansions is a young group. But at the same time, you opted to include Tony Marino, a well-established player, on bass. What was behind the idea of surrounding yourself with younger artists on other instruments but not bass?

DL: Ultimately, I wanted to make sure that the bassist holds the drummer right and Tony is great at that. I wasn’t going to go out there with a bunch of musicians without someone else who can also help tie things together. I’ve recorded more with Tony than with anyone else, except Richie. He’s one of my indispensable guys.

PG: The band’s album right before Selflessness was Earth (Whaling City, 2020). On that album, the focus was heavily on using sound textures to create ambient textures. Do you feel like that emphasis on textures influenced Selflessness?

DL: Earth is definitely a texture record. You’re not playing C7 as a harmonic point anymore. Instead, you’re playing the movement and the feeling of movement. I really enjoyed that record. Of course … just like most things we do … it didn’t get any attention.

But Selflessness is primarily a jazz record, as it should be. I mean some of the arrangements definitely cast things in a different light than people may be used to but at its core, it is a jazz record. We actually recorded it a few years ago. I just wanted to make one more Coltrane album, even if it meant putting the recording in my pocket for a while.

PG: You play soprano on the entirety of the album. Of course, you are probably best known for your work on soprano. What do you think draws you more to the soprano compared to other instruments you play like the tenor, flute, or clarinet?

DL: It’s a straight horn. The straightness of it, like a trumpet, leads you to different avenues. I don’t know why, but it does. I do feel physically different when I play soprano. I haven’t touched the tenor in a year and a half or so now. But it’s not the first time I put the tenor aside. I had quit the tenor from around ‘80 to ‘95. I took a break at that time for a variety of reasons, one being that I felt playing soprano would allow me to have more of an effect on jazz music because there weren’t that many soprano players in 1980-81. I had already gone through a period of my life where I had played only soprano. With the Expansions band, I figured I would basically be the straight guy and the other guys would sort of paint pictures around me.

PG: What motivated you to have a second woodwind player in the band?

DL: Well, Matt [Vashlishan] is very adaptable. He’s also very good with electronic instruments. I love the colors he gets on them. That is part of the charm of Selflessness for me, that we are playing in a contemporary language on tunes that are identified with the jazz repertoire. I thought it would be a nice contrast between those electronic sounds and some of the more traditional and changing instrumentation of the group. There is a lot of variety on that record which is my usual MO.

PG: Which in some ways goes back to the eclecticism of sound you were mentioning earlier. You have recorded a wide range of music across many albums. As a leader, you have over 250 albums to your credit. Are there two or three that you are particularly proud of?

DL: There are a few with Richie that stand out, especially Forgotten Fantasies (Horizon 1976). And, of course, Lookout Farm. Also the albums I did with Quest, particularly Of One Mind (CMP, 1990).

But I would say that The Loneliness of a Long Distance Runner (CMP, 1986) is one that really stands out to me.

It was dedicated to [Steve] Lacy. It also reflected me dealing with being an artist at midlife. I was 40 when I recorded that album and I wanted to express what I feel all artists deal with. The idea of a long distance runner and what he or she has to encounter is very similar and could be a metaphor for what we do as artists and what I specifically do with the saxophone. It was a way of painting a picture that was very autobiographical. (A lot of my music is autobiographical). Musically, the album was extremely challenging. Trying to stay in tune with four sopranos was definitely special. I also had to write more for it than many other projects I’ve done. All soprano, all overdubbed. At one point we were playing with eight sopranos but I really didn’t want to turn it into a circus. It was the text that really tied it all together. I wrote about the race; the long distance runner as a metaphor for the artist’s commitment to beauty and truth. It fascinates me how we become this thing called an artist and then we have to figure it all out!!

More information about Dave Liebman can be found on his website.

Dave Liebman’s Expansions Quintet’s new album, Selflessness, is now available on Dot Time Records. Empathy, his five-CD set with longtime collaborator Richie Beirach and special guest Jack DeJohnette, can be purchased in our Amazon Affiliate store.

Leave a Reply