|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

The 1990s was a period of change. The geopolitical order in place for nearly half a century ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The first American president to be born after the Second World War took office, bringing different attitudes and policies to the office. Rapid technological development – specifically the rise of public access to the internet – brought together people from across the globe. Unsurprisingly, one can also find new influences in the music of the era.

The decade finds a rise of new jazz artists. Looking at the late 1980s, one would likely expect the “smooth” sounds that came to dominate the Festival’s lineups to heavily guide this new class. But while “smoother” artists would appear sparingly at Newport during the ensuing years, the movement’s power was greatly diminished and generally not representative of an overarching musical trend. These new musicians also did not merely further the neo-traditionalist conceptualization of jazz. While they looked up to tradition, they were not as closely bound to adhering to it as an artist like Wynton Marsalis. Instead, the “young lions” – many of whom first became aware of the Newport Jazz Festival in their youth – were steeped in history but open to bridging it to new sounds and ideas.

In 1990, a pending generational shift had not quite taken effect at Newport. While Wynton Marsalis had returned, the vast majority of the lineup consisted of long-established artists: the Count Basie Orchestra under the direction of Frank Foster, George Benson, Joe Zawinul with the Zawinul Syndicate, McCoy Tyner’s Trio, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, Tito Puente and his Orchestra, and legendary salsa vocalist Cecilia Cruz. But the absence of any “smooth” bookings clarified that a change in the Festival’s general approach was on the horizon.

Instead, one can view 1991 as the birth year of the new era’s emergence at Newport. Most of the lineup consisted of artists steeped in the blues or R&B – Lou Rawls, Etta James, and John Lee Hooker with John Hammond.

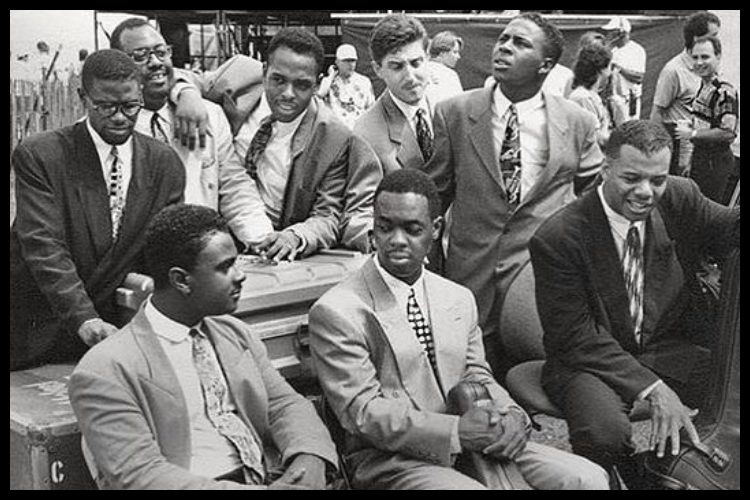

However, it also marked the Newport debut of Dominican pianist Michel Camilo, who would later appear several times over the ensuing years. Further, it was the year that brought a super-group of “young lions”; The Jazz Futures. The short-lived – they only recorded one release – octet consisted of artists many viewed as best representing the next generation: trumpeter Marlon Jordan, saxophonists Antonio Hart and Tim Warfield, guitarist Mark Whitfield, pianist Benny Green, and drummer Carl Allen. While each ultimately forged formidable careers in music, the remaining two members of the group particularly stand out.

First is the late Roy Hargrove, who is often heralded as ushering a new era of music by combining jazz, hip hop, R&B, and neo-soul. From his membership in the Soulquarians to his RH Factor, he emphasized the equality of all musical styles. This viewpoint would hold immense influence over many of today’s musicians. As Ambrose Akinmusire would later note:

The other member, bassist Christian McBride, would ultimately perform and record with an incredible range of artists from all over the musical spectrum, from James Brown to Paul McCartney to the Roots to Herbie Hancock. He would also later take on a role of central importance for the Newport Jazz Festival, serving as its Artistic Director and the host of the Festival’s weekly online interview series.

The 1991 Festival’s combination of jazz-adjacent artists and “young lions” also shaped the 1992 lineup. Roberta Flack sang in a style touched by R&B and soul music. Funk was provided by two groups. The first was the large ensemble Tower of Power. The second was James Brown’s former backing band, the J.B. Horns. Many of the group’s members – including Maceo Parker, Pee Wee Ellis, and Fred Wesley – returned to Newport for their first time since Brown’s legendary performance in 1969. Younger artists included the return of Carl Allen, who was appearing with The New York Jazz Giants, an all-star septet consisting of artists primarily under the age of 50: Jon Faddis, Lew Tabackin, Bobby Watson, and Ray Drummond. Iconic pianist Thelonious Monk’s son, drummer and then-Blue-Note-artist, T.S. Monk also performed. As did Bobby McFerrin, well known for his unique polyphonic overtone and acapella singing, who is also the son of Robert McFerrin Sr.; the first African-American man to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. The vocalist’s set was a fascinating duet with drummer-pianist Jack DeJohnette. Other artists on the lineup included Shirley Horn and McCoy Tyner with his Big Band. Max Roach made his first appearance in the city since his Freedom Now Suite with Abbey Lincoln blew audiences away in 1960. The weekend began at the Casino with sets by Cleo Laine with the John Dankworth Quartet and harmonica player Toots Thielemans joined by Fred Hersch, Harvie Swartz, and Adam Nussbaum

The focus on the new generation of artists seemed to pay off for the Festival, often resulting in sold-out festivities at the Fort. Entering into its fourth decade of existence, the Newport Jazz Festival- joined by a powerful sponsor in JVC – only further grew in its significance among the major music festivals in the world. With the election of Bill Clinton, a jazz fan as President, it was the perfect time to bring the Newport Jazz Festival back to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. On June 18, Wein presented a wide range of artists at the White House: Michel Camilo, Rosemary Clooney, Clark Terry, Joshua Redman, Al Grey, Dick Hyman, Illinois Jacquet, Charlie Haden, Elvin Jones, Bobby McFerrin, Dorothy Donegan, Joe Henderson, Herbie Hancock, John Lewis, Christian McBride, T.S. Monk, Red Rodney, Jon Faddis, Jimmy Heath, Grover Washington, Jr., and Joe Williams. In the closing moments of the event, even Clinton himself was persuaded to add his own saxophone to a version of Miles Davis’ “All Blues.”

Of those who performed at the D.C. event, Michel Camilo and Joshua Redman both appeared at Fort Adams later that summer. It was twenty-four-year-old saxophonist Joshua Redman’s first time at the Festival and shortly followed the release of his self-titled debut album as a leader (Warner Bros., 1993). As the son of another horn player, Dewey Redman, who had performed with Ornette Coleman during the Festival’s New York years, discussions on a perceived passing of the torch were inevitable. But his quartet with McBride, Brad Mehldau, and Brian Blade forged their own way ahead.

Michael and Randy Brecker, who had reunited as a band the prior year after an eleven-year hiatus to record Return of the Brecker Brothers (GRP, 1992), were also on hand. Other artists that weekend included Ray Charles, George Wein’s Newport All-Stars, and John Scofield’s Quartet featuring Joe Lovano.

Lovano would return for the 1994 Festival, this time as a leader. In addition to his striking work with Paul Motian and Bill Frisell, the saxophonist was becoming well known for his exciting work as a leader. Quartets: Live at the Village Vanguard (Blue Note, 1995), today still held among his top recordings, captured Lovano around this time of his career. The 1994 Festival also had heavy representation from New Orleans with the return of the Dirty Dozen Brass Band and Wynton Marsalis as well as the Newport debut of another young trumpeter, Terence Blanchard. Cassandra Wilson, soon after releasing Blue Light Until Dawn (Blue Note, 1993), also appeared at Newport for the first time. So did pianist Marcus Roberts, vocalist Rachelle Ferrell – best known for her access to the whistle register – and fusion group The Yellowjackets. Returning artists included Buddy Guy and George Benson.

Since moving to Fort Adams in 1981, the new incarnation of the Newport Jazz Festival continued – just like the underlying music itself – to thrive and grow instead of being trapped in its illustrious past. Its sister festival, the revived Newport Folk Festival, likewise excelled at finding an audience. The time proved ripe to expand the Festivals’ offerings in the city.

The 2021 Edition of the Newport Jazz Festival will take place from July 30th to August 1st at Fort Adams State Park. We plan to have live coverage of the event. More information can be found on the Festival’s website.

Leave a Reply