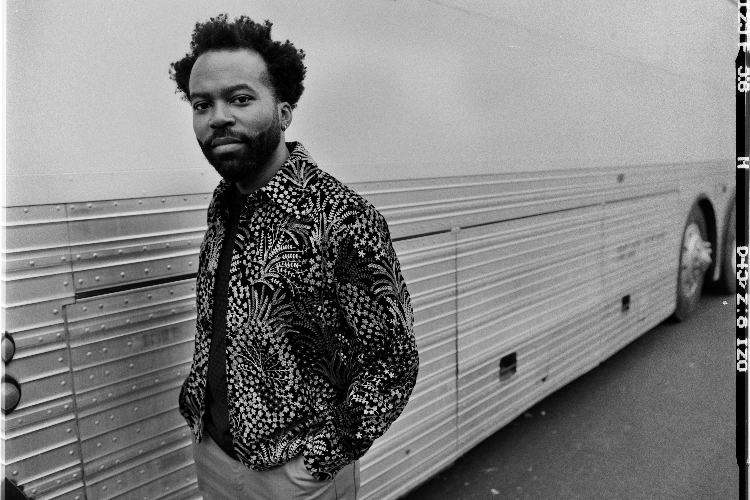

Solo? : A Conversation with Josh Johnson on ‘Unusual Object’

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Certain instruments seem destined for solo explorations. Perhaps the best example would be the piano, where a single artist can easily use one hand to accompany the other. Less stereotypical, yet no less significant, are the long run of solo saxophone recordings. Many horn players over the years have found that playing alone can provide a freedom of expression unobtainable otherwise. Hence, it should come as no surprise that some of the instrument’s most iconic figures – from Coleman Hawkins’ groundbreaking “Picasso” to the laid-back cool of Lee Konitz’s Lone-Lee (Steeplechase, 1975) to the audacity of Anthony Braxton’s For Alto (Delmark, 1971) – released some incredible solo saxophone recordings. This legacy has continued to the present day through releases by artists including Branford Marsalis, Jaleel Shaw, John Zorn, Steve Coleman, Sam Newsome, and Colin Stetson. Upon first blush, Josh Johnson’s latest album, Unusual Object (Northern Spy, 2024), would also seem to follow this lineage. Or does it?

To be technically correct, Johnson is the lone instrumentalist performing on Unusual Object. But his alto, while the sole horn, is only part of the sonic collage presented on the album. Johnson incorporates samples, electronic effects, and pedals in ways his predecessors generally did not. These additional inputs allow him to create wholly distinct sound environments that are paradoxically inviting yet elusive. The result is pieces like “Marvis” where the saxophonist’s dulcet melody glides through a bubbling, warped, and, sometimes, murky terrain. Or “All Alone” where a gentle repetitive electronic motif creates an ambiance of loneliness and desolation over which the sax lays out its bluesy cries. If one were to hear the interactions between instruments by itself, they would likely never guess there is a single artist playing them all.

Where Johnson’s immediately preceding debut, Freedom Exercise (Northern Spy, 2020), blurred the line between through composition and improvisation, Unusual Object‘s primary objective seems to be to question the conceptual underpinnings of a solo album. If one hears many voices on a solo record but they all come from the same narrator, is it still a solo recording? Further, as emerges in our conversation with Johnson, there are the collaborators behind the scenes. These contributors are essential to the album’s creation and can be heard in less tangible ways on the recording. So, what exactly is a solo record? Can any album truly be a solo recording given the team needed to release the full artistic vision to the world?

Johnson is well suited to explore such interactions between the individual and their community. He has an identifiable individualized voice on his horn. But he’s also logged significant time collaborating with some of today’s best artists, including Makaya McCraven, Jeff Parker, Meshell Ndegeocello, Nate Mercerau, Marquis Hill, and Leon Bridges. We sat down with Johnson to discuss Unusual Object and the ambiguities of a solo saxophone recording.

PostGenre: Before we get into Unusual Object, congratulations on the recent Grammy win with Meshell Ndegeocello. [Ed note: Johnson produced and performed on Ndegeocello’s Omnichord Real Book (Blue Note, 2023), which won the first-ever Grammy Award for Best Alternative Jazz album].

Josh Johnson: Thanks, I appreciate it.

PG: How did you get set up with Meshell?

JJ: We met a long time ago. I’m not entirely sure how we did. We probably met through Jeff Parker. There was a period around 2016 or 2017 where Meshell was out in [Los Angeles] more often. She and some of the other people from her band would frequently come to our – me, Jeff, Anna [Butterss], and Jay [Bellerose] – gigs at [the Enfield Tennis Academy]. Meshell and I met through those shows, I’m sure.

PG: You have worked frequently with Jeff. What is it that makes you want to work with him so often?

JJ: Jeff’s my dude. I’ve known him for such a long time. I’m thirty-four, and I think I met Jeff when I was only seventeen, long before we’d ever made music together. I think I met him when I’d snuck into one of his shows with my then-girlfriend. Fast forward, I went to school and was living in Chicago, and Jeff and I both started playing a little bit there. We both moved to LA around the same time and are kindred in many ways.

Even as a teenager, I was very drawn to Jeff’s music. Even then, he had a clear voice that very much spoke to me. Jeff performs in wildly different settings and always sounds like himself, but not in a manner that ignores his surroundings. He can move between many different sound spaces.

PG: You also have an identifiable voice. While Unusual Object is different from your prior works, your voice is still recognizable. Have you worked hard to create and maintain an established voice?

JJ: I appreciate that. It’s an interesting thing. I teach occasionally, and some students have asked me how to create something unique and personal. I guess I’ve always been interested in creating something personal. But it feels like a natural extension of my exploring things that I’m interested in. I try to vividly imagine stuff and then attempt to clearly express what I envisioned. My experience in music has never really been centered around trying to find a person who is the model for something and trying to imitate them. I’ve been more interested in drawing inspiration from other people and making something my own that is a little more personal.

PG: In terms of drawing inspiration from other musicians to make something personal, there is a long lineage of solo saxophone albums. Did those recordings inspire the creation of Unusual Object?

JJ: Well, I didn’t initially set out to create a solo record. Sometimes people decide from the outset to create a solo record, but I didn’t here. I just had some musical ideas I wanted to express, and they seemed to come out better when I was playing solo. A solo record wasn’t something I initially planned to make.

As far as the lineage you mention, I don’t know how much it has influenced this record. I have often found myself asking the question of what exactly is a solo record. I am playing all of the parts, but there is not only one instrument played. I do love solo saxophone albums. They are important to me, and I have learned a lot from them, but they were not a direct reference for this record.

PG: The electronics certainly add an element not found on most solo saxophone albums. What is your process for selecting and incorporating electronic sounds into the music?

JJ: Before I answer your question more directly, my process has evolved over a long time. A lot of it happened in the space of the Enfield Tennis Academy band. Adding electronics is something that has interested me since I was a teenager.

My process is to add things very slowly. It’s not dissimilar to learning an instrument, where you want to understand the range of sounds within what you are using. Once you do that, you can have flexibility with how you use electronics. It is about developing an imagination and seeing how it incorporates the tools at your disposal. I’m often looking for stuff that’s responsive and flexible.

And then, often, I’m looking for the tool’s limits and trying to understand the interesting stuff that happens when you don’t do the thing the tool is trying to lead you to. For me, trying to use things in a way different from what you are being led to is the most exciting part of using electronics. I love using things meant to do one thing and trying to figure out how to use it differently than how it was intended.

Back to [the Enfield Tennis Academy], my experiences there have been helpful because my interaction with all that stuff was always through improvising. If I wanted a delay effect, I had to figure out how to do so in real-time. I gained so much from exploring the stuff in that space.

PG: When you are composing pieces for Unusual Object, did you start with the saxophone and figure out what electronics fit best around it, or did you create electronic ideas first and work around them?

JJ: It depends. It changes with every song. Some people follow a consistent process, but I feel a need to be able to hop around.

On this record, there were a few things that started with solely the saxophone. But, live, the process of combining sax and electronics is an interactive one. Things aren’t always moving in a parallel direction, which is very interesting to me. Often, I have everything there to explore many zones simultaneously. But, occasionally, I find myself a little limited or stuck in the same idea. When that happens, I pivot by picking up another instrument.

PG: In a more general sense, do you feel that your experience with electronics has changed how you approach the saxophone or vice versa?

JJ: Yeah, for sure. As much as I love saxophone and love listening to saxophone players, an increasing fascination of mine has been hearing something sonically that you can do with electronics. I’ve tried to bring some of those sounds over to the saxophone, as well. The electronic stuff and my saxophone performance inform each other. It’s hard to give a super concrete example, but I feel like each influences one another.

PG: In a broader sense, how do you feel you have changed or developed the most since Freedom Exercise?

JJ: That’s a good question. I know a lot of life happened between the two. When I worked on Freedom Exercise, up until recently, was working on not only my own music and those of others but also serving as a musical director. Serving as a musical director provides you with a different perspective. There were some things I felt were coming into focus on Freedom Exercise that were seeds for what you hear on Unusual Object. Many of the things you hear on this record followed threads I put out on the last one but developed them a little more. I also feel – not to make a pun on the last album’s title – a little freer now than I did back then. I now allow myself to explore different zones.

The saxophone is a funny instrument. I love it. It’s beautiful. It’s fickle. One of the things that guided me in adding electronics is how limiting the saxophone can be. In many settings, the saxophone’s role is to play a melody and then a solo. A big reason I got into trying to incorporate more effects and electronics was that I thought it would be cool to be involved in music in a way that’s not solely as a soloist or someone putting together a melody. Instead, I wanted to interact with music in a more foundational way. In terms of growth between the two records, I still don’t have answers but do feel a little more confident in exploring music in different ways.

PG: A little earlier, you had mentioned serving as musical director. That was for Leon Bridges, right?

JJ: Mhmm.

PG: Did you take that role, in part, because it also let you get involved with music in a way that is different from soloing and providing melody?

JJ: Yeah, for sure. I’m grateful for that experience, and it taught me a lot about sensitivity to the big picture and how to create an artistic arc. It’s not that I never paid attention to these things before the experience. However, it allowed me to spend some more time addressing many of the other elements of music and understanding my own preferences. The experience helped me develop my taste, as well.

PG: As a final question, while most of the album has you entirely by yourself, “Quince” also contains drum samples by Aaron Steele. What made you decide that incorporating someone else’s work into the project fit with the rest of it?

JJ: I did not think about it in those terms necessarily. The track came about naturally. Aaron is one of my dearest friends and a very regular collaborator. He also played drums on Freedom Exercise. We also encouraged each other creatively from the [COVID-19] pandemic onward. There was a period where we would check in with each other every week and give each other creative assignments.

All of that is to say that it felt very organic and natural to include Aaron’s samples. The track’s inclusion also speaks to what we had discussed earlier, that the new album wasn’t initially a solo record.

I do want to say, however, that Paul Bryan, who produced the record with me and who mixed it, was incredibly important to this project. He was also very important in creating Freedom Exercise. He’s such an incredible musician and bassist that though he’s not playing on Unusual Object, his presence is still felt on the record. His taste and intuition were incredibly important to the sound and shape of the record. Paul was critical to framing and giving everything a place sonically. It was interesting for the majority of our collaboration to be in that space, compared to playing together. So is Unusual Object truly a solo record or is it a collaboration between me and some friends? It is kind of both.

Unusual Object is now available on Northern Spy Records. It can be purchased on Bandcamp. More information on Josh Johnson can be found on his website.

Photo Credit: Robbie Jeffers