|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

In this second part of our conversation with Sonny Rollins, we do a deeper dive into one specific area we circled in the first. Music plays a significant role, including some coverage of his various outings as a sideman and his retirement from performance. But in our continued discussion, the focus is more on Rollins’ perspective on life in general. By digging into his philosophical views, we can obtain a fuller view of the Saxophone Colossus’ output, one beyond specific notes or phrasings. We can get to the core message of his life’s work and, in the process, hopefully, draw out even more color in his already vibrant art.

PG: Is there anything you had hoped to explore musically but did not?

SR: Yeah. But that’s that. Who knows? When I come back next time, maybe I won’t be a musician. I don’t contemplate being a musician next time. I don’t really contemplate anything about the next life. I’m not a fortune teller.

It’s not about that. It is about my whole journey. Each of us is on our own journey. You may have to live many times before you even get an idea of what everything is all about. The only thing I know is that I want to be a person that lives by the Golden Rule. Do unto others as you would want them to do to you. That is a standard message that all religions preach before they go off into their specific wants and desires. All religions – Taoism, Buddhism, Protestantism, Catholicism, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, whatever – teach the Golden Rule. Each one of them. All religions ask us to treat one another with respect. But then each goes off into their own practices. Things like that you can’t eat certain foods or must pray in a manner specific to that faith. In a way, these specific things segregate religions from each other. And those divisions are part of why the world is the way it is, with people killing each other. But they all preach the central idea of treating other people in the way you want to be treated. There is nothing new about that. It is as old as any other structures we have.

PG: Unfortunately, we human beings still struggle with treating others with respect.

SR: I know. I don’t know why that seems to be the way we were made. Maybe struggling with it is part of why we have to learn. If we didn’t struggle, everything would be hunky-dory. There would be no wars in life. There would be no hatred in life. Until we get past our struggles, those things won’t go away. How you get past them is too much for me to contemplate. I’m not God. But I do know that is the way it is and we need to learn.

PG: One of your albums that stands out is Without a Song: The 9/11 Concert (Milestone, 2005). Only a few days after 9/11, an immense and tragic act of hatred, you left your home near the World Trade Center to perform in Boston. Your primary focus was on bringing people together after something truly horrible. Where do you see music’s role in spreading the Golden Rule?

SR: I think how people responded to that concert spoke to the power of music. I’m so happy that the album came out.

I lived six blocks away from the World Trade Center on 9/11. So, I was right in the middle of it, so to speak. I heard the first plane come in as it was crashing into the first tower. I heard the first plane come in and then the other plane, the whole thing. I lived up on the top floor – the 39th floor- and had to be evacuated the next day. I was glad people liked the concert and felt a closeness to it. I felt very close to it, being right in the middle of the events at the Trade Center. The attack reminded me of the war movies I used to see as a boy back in the 40s.

PG: It seems you have a strong connection to film. We discussed how cowboy movies influenced Way Out West. Now you are referring to living near the World Trade Center as being in a war movie. You also did the soundtrack to Alfie (Impulse!, 1966). What are your thoughts on how music interacts with other art forms, like film?

SR: Well, for movies, music is essential. In any narrative, it is great to have some good music to highlight things.

I have loved music since I was a boy. When I first heard Fats Waller, I realized that music was my path in life. It’s not everybody’s path, but it was mine. Everyone has something that affects their life in a positive, even religious way if you want to use that word. Music was it for me, and it still is. I am so happy that I had a chance to play it for most of my life, to play with some great musicians, and to make a little contribution of my own. I am so blessed.

That is why I got so angry when I first found out I could no longer play my saxophone. But at some point, I finally got myself together and said to myself, “Look, shut up Sonny, what are you talking about? You’ve had a wonderful chance to make something out of this thing that you have loved so much.” From then on, I decided I would stop feeling bad that I could no longer play.

PG: While your respiratory issues keep you from playing saxophone, you also play a little piano and violin. Have you ever considered continuing to make music on those instruments?

SR: [laughing] Both the violin and the piano bring back special memories for me.

My brother, who was five years my senior, was a concert violinist. I heard him practicing all the time.

As far as the piano, we always had a piano in the house growing up, and my sister played it. I also played the piano very early on. But I don’t really play it. I just mess around with the piano. I still have a piano upstairs in my house, along with flutes and other kinds of instruments. I can’t play the wind ones due to my breathing issues. I could play the piano but I just haven’t gotten into it. The place that I reached in my saxophone studies was somewhere special to me, and being cut off from it eliminated a lot of aspects of my musical thought. I just haven’t been able to play anything else.

But, ultimately, everything is good. My life is good. Not being able to play music got me deeper into my spiritual pursuits. I had a spiritual sense early on. I was born into it and started studying Buddhism in the 1950s. But not being able to play has allowed me to focus even more.

I am trying to learn every day. It is one thing to say that you should be good to your neighbors and another entirely to actually do it. You have to learn how to be good to them. I’m learning every day how to live by the Golden Rule. It really takes learning. As I said, who knows how many lives I have been here. It may have even been a trillion lives. And I might be here a trillion more lives until I learn the universe’s plans for what it is all supposed to mean. Realizing the plan and getting there takes time. But I’m very grateful that I have learned what my life has taught me.

PG: You mentioned a little earlier the other great musicians you were able to work with throughout your career. We could go through the long list. Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and Clifford Brown, just to name a few. But is there anyone you worked with that you felt did not get the attention their music may have deserved?

SR: Well, I can’t think of anyone specifically off hand. But I think a lot of people I worked with didn’t get enough notice from the public. Jazz has always been underappreciated. Jazz has gone through a long, long history of being denied.

We’ve finally reached a point where jazz is considered by many people to be on the same level as European classical music. It’s finally being recognized in America as being equal to music by Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Dvorak, Debussy, and all these other composers people revere. It may not be there completely yet, but it is certainly closer to that than ever before.

But, at the same time, jazz has always been a difficult field. Most people today don’t know anything about the great jazz musicians from back when. That’s because we have to compete against commercialism. So much music is not released because it isn’t easily sold as a product. I don’t see a lot of people listening to jazz the way they listen to the more commercial music that comes out today. Jazz has gotten to a point where it has been recognized as the very, very superior music form that it is. And that’s great. But when I turn on the radio, it’s not jazz that comes on.

PG: One name that keeps popping up throughout your career is [bassist] Bob Cranshaw. You worked with Bob for almost five decades. What was it about his playing and musical ideas that you felt resonated so well with yours?

SR: A lot of people ask me that. I got involved with Bob was because he was a good reader. I would bring in a lot of obscure tunes from old movies and things like that. Bob was a good reader of music and could handle the music.

I also found that I was the only jazz guy who could play calypsos and they became a very big part of my performance. When I would play calypso in concerts, the crowd would go wild. Bob Cranshaw was one guy who could play calypso. If we were in a concert and the music wasn’t getting to the crowd, we could play a calypso and bring everyone into the music. Bob could do that. That is one of the aspects of our relationship that I have never expressed to anyone before.

PG: Calypso and other Caribbean music have long influenced your music. Many jazz recordings, over the past decade or so, borrow ideas from other music from around the globe. Do you feel that bringing in musical ideas from other cultures has always been a part of jazz?

SR: I do think jazz can pull in a lot of different music. I can play calypso and stuff like that in my music. But I love all kinds of music, some of which you may not even notice in my music. As you travel and live to be my age, you hear all kinds of music. Each place – Poland, Mexico, or wherever- has its own indigenous music forms, and that’s all good. Whether Indian ragas or music from Ireland, all music has a way of reaching the soul. But I just feel like jazz opens up a whole thing. Jazz has so many ways it can reach you.

PG: We have only scratched the surface of your career. Have you ever considered writing an autobiography to cover it all?

SR: I’ve thought about writing an autobiography, especially now. Two books coming out soon about me. One should be out anytime now. They are doing the pictures, and it is supposed to be a 600-page book.

As for the second one, they are doing the pictures for that one right now as well. They got a lot of the pictures that were in The Schomburg Museum [The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; a part of the New York Public Library system and which owns Rollins’ personal archives] for that one.

I don’t know what either of the books will say, but I do know that I would like to write an autobiography sometime that explains my quirks, what I tried to learn, what I didn’t learn, what I wish I had learned, and what I had accomplished. Yeah, I would like to write that sometime.

PG: And it seems like you are continuing to learn. Presumably, some of those lessons would be in such a book as well.

SR: Beyond all the musical things, I have always wanted to prove myself. The authors of these books that are coming out mentioned to me that throughout my life it seemed like I was always trying to get better and be a better person. Even back when I was trying to get away from using drugs, I was trying to be a better person. I was always trying to be better. I still haven’t yet made it.

I didn’t make it as far as the music was concerned. I was practicing constantly but didn’t get to the point I wanted to by the time I had to stop playing. I also haven’t gotten there as a human being. But I’m still alive and still trying to get there. I don’t think I will become a perfect human being in this incarnation, but I’m still learning and trying to reach that goal.

PG: It does not seem like any of us will be perfect in this life.

SR: I guess not. That’s right.

But at least we are going to have more chances. That is the salient point. Nobody is going to be perfect in this lifetime. This lifetime is so full of things like ignorance and hatred. Humankind is not ready for perfection. But we will have other chances. That is the beauty of the theory of reincarnation. We’ll be back. We’ll be back. We’ll be back. We’ll be back. However long it takes.

God, or whatever you want to call it, is good. There’s nothing wrong with the world. Whatever is bad is from our ignorance and we have to try to get away from that. It’s not God. It’s us. It’s all good. And we are going to have a chance for things to get better. We will get a chance to make our understanding of whatever we are involved in better. I just try to be as good as I can in this life, not worry about what’s coming next and all that stuff. It’s not my business. My business is this world; to try to make Sonny Rollins a more advanced human being who can help other people.

That is the reason I think we are all here really, to help others. Everything is part of some good plan. Even if you don’t reach the level you desire in your life, there is nothing to feel bad about. This world is meant to be just as fucked up as it is. There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s meant to be the way it is, and we are meant to be here trying to deal with it. Keep fighting for whatever you think is right. If you don’t get it now, you are going to get it later.

More information on Sonny Rollins can be found on his website.

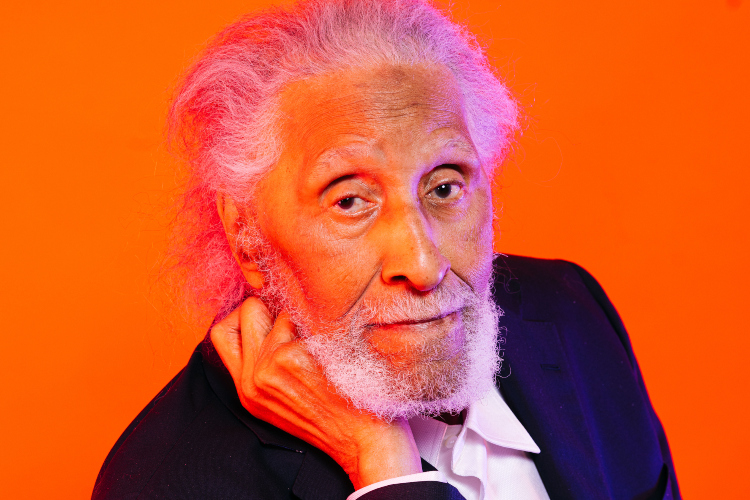

Main photo by Mamadi Doumbouya. A special thanks to Terri Hinte.

Leave a Reply