|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

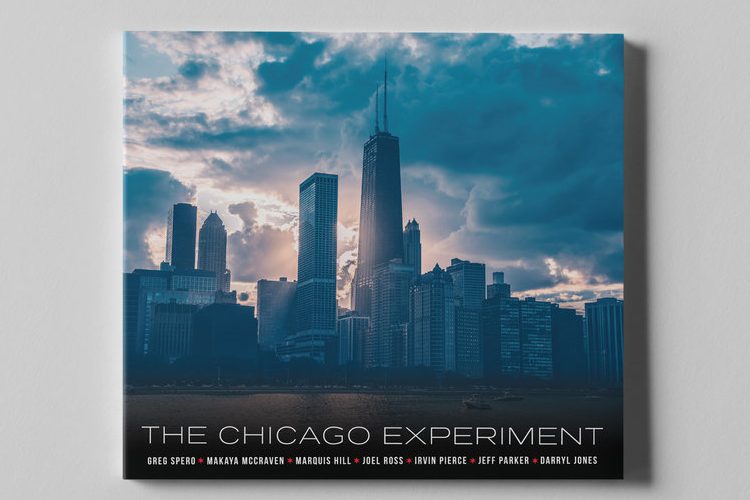

In 2001, Ropeadope Records released The Philadelphia Experiment, a unique collaborative effort by three artists from the city of Brotherly Love who built off of their community’s rich musical history to create something new. Part of the project’s success came from the diverse musical backgrounds of its three leads. From hip hop and R&B came Amir “Questlove” Thompson. From classical and jazz, Uri Caine. And straddling all areas, Christian McBride. After their meeting met rave reviews, two follow-ups followed, each with a different cast of artists; The Detroit Experiment (Ropeadope, 2003) and The Harlem Experiment (Ropeadope, 2007). While the liner notes to Harlem teased listeners to “look for new experiments”, for over a decade there was radio silence. Occasionally rumors would pop up, but nothing ever materialized. Now, more than two decades after the original Experiment, a new trip was planned to one of America’s premier musical cities; Chicago. As a result of the “Great Migration” of poor workers from the South, the Windy City has birthed many branches from the great tree of Black American Music, including electric blues, avant-garde jazz, soul, house, gospel, and Chi-town rap. Greg Spero’s The Chicago Experiment (Ropeadope, 2022) draws from these traditions but, like its predecessor albums, uses them to carve a path all its own.

A testament to the continued strength of their hometown’s musical scene, the septet presented on The Chicago Experiment is nothing short of impressive. From original compositions to reimaginings of Gil Scott Heron and Blue Note Records, drummer Makaya McCraven has established himself as a powerful force in improvised music. Marquis Hill – who regularly fuses jazz, hip-hop, R&B, Chicago house, and neo-soul- ranks among the best trumpeters of his generation. Joel Ross is a master of the vibraphone, breathing new life into an instrument far too often overlooked outside of Lionel Hampton, Milt Jackson, and Bobby Hutcherson. Saxophonist Irvin Pierce has played a significant role with the group Resavoir and with Junius Paul. From Tortoise to Rob Mazurek’s Chicago Underground to The New Breed (International Anthem, 2016), guitarist Jeff Parker needs no introduction. On bass, Darryl Jones, whose credits include Miles Davis, Sting, and an almost thirty-year run with the Rolling Stones.

In addition to being a gifted pianist, Greg Spero has been a fascinating figure on the business side of music. He’s been called “a new breed” of record executive, partly due to his start-up weeBID, the world’s first fan-initiated crowdfunding platform. Spero also runs his own label, Tiny Room, which tries to showcase the transmutability of all genres. And he has been at the front lines of using new technology – whether Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) and cryptocurrency or Virtual Reality (VR) concerts. We sat down with Spero to discuss The Experiment, his influences, and the coming changes emerging technology may bring to the music business.

PostGenre: How did The Chicago Experiment come about?

Greg Spero: I was already planning a record with all of my Chicago guys when Ropeadope approached me. There was an interesting synergy with this album that seemed written in the stars. My last project, Spirit Fingers, was very unlike this album. It was very young, centered on the virtuosity of individual players, and consisted of really through-composed material. Spirit Fingers was super high energy. I toured with that group for a while and loved it.

But I also felt like an aspect of who I am was missing in music for Spirit Fingers. The more I reflected upon that, the more I realized that what was missing was the communal fabric of the Chicago music scene. In the scene, you put your identity directly into the fabric of a social network so that it’s not just about you anymore. Instead, what matters is the group and what it can create together. This collective is what makes Chicago so special and differentiates it from cities like LA or New York.

There is also a sense of grittiness to Chicagoans. I believe some of that comes from the winters we must endure. But it is also partly due to the fact the city’s infrastructure is fairly limited. A lot of the stuff we had to build in Chicago, we did it brick by brick. Through that process, we Chicagoans learned to be great builders. That includes building musical ideas.

But we are also deeply interconnected with the people in our community, which helps us get through the hard times. There is a lot of that in the Chicago artists of my generation as well as the older ones that mentored us. And it can also be seen in a generation younger than me that builds on those communal ideas and is just killing musically.

PG: Like Joel Ross.

GS: Yeah, Joel is a great example. And across the generations, we have all found our own way into the social and communal fabric of Chicago. That fabric has shaped who I am as a person, the music I love, and my mentality in approaching music. So, it was natural for me to highlight that aspect of my music with The Chicago Experiment.

PG: You are also very interested in technology. One of the great things about the internet is that it allows people around the globe to communicate with one another. However, these dialogues across geographic boundaries may also deemphasize local bonds between people. Do you feel like technology harms the cultural fabric of places like Chicago to some degree?

GS: I think it can, but technology can also highlight the community. What matters most is how people use technology. Technology only has the effect that we as human beings decide it should. We can use it for good or bad. The technology itself is neutral. Any technology can easily create either catastrophe or beauty. It all depends on how you use the technology. We can split atoms to create nuclear bombs and, potentially, end all life as we know it. Or we can split them to create nuclear power.

Another example is the most recent political upheaval in our country. People were at each other’s throats, and it was disgusting how people were treating one another. I think some people used technology to rip apart communities, but it wasn’t the technology itself that did that. The technology merely enabled people to take action on their preexisting destructive desires. And, on the flip side, technology has allowed places like Chicago to be highlighted in a beautiful way.

The use of technology for music is the same way. I mean, look at Spotify. Many artists have been very upset that Spotify even exists. They don’t make nearly as much money from streaming royalties as they did when they sold physical media.

PG: Like CDs or vinyl.

GS: Right. And those artists who have spoken out against Spotify have valid concerns. But the reality of the situation is that the money has simply moved out of physical media. It’s gone elsewhere and we haven’t quite completely figured out how to manage that shift yet. Now that information is everywhere, we are not going to be paid the same way we did back when the distribution of information was a scarce asset.

There are so many ways artists can make money now that were not available in the past. This shift is one of the reasons I created weeBID, a platform that tries to find ways to better connect creators with their fans. We can communicate and share information on an almost immediate synchronous level through weeBID. Among other things, the platform helps crowdfund ideas for creators in a way that more directly connects them with their followers.

And, I think we are just scratching the surface. We as an industry haven’t fully fleshed out new revenue models. But there are several people, myself included, who are working hard to form those new kinds of models. I think we are about to go into an era where creators will both be given more control over their art and make more money than ever before.

PG: One of those newer revenue models is the sale of NFTs. As someone who has been at the forefront of using NFTs, how do you think they will impact music in the long term?

GS: That is a very good question. I think NFTs reflect the fact that everything we do as a species is starting to emphasize things that are representative of something else. It’s a really interesting concept.

Consider money as one example. At the very beginning, people used to barter and trade things with one another to get what they wanted. But as the economic environment evolved, we needed a more universal method of exchange. And so, society started to use scarce assets like gold to facilitate exchange. Over time, these scarce assets became paper currency. And now we are at a place where digital assets represent that paper.

But, with money, we are at just the tip of the iceberg in terms of using representation instead of physical items. Nike is now even selling NFT shoes. You can’t wear them because they don’t exist in a fungible way. But the NFT is still representative of the idea of a shoe. Someone can own it.

For the first time, we have an ecosystem that emphasizes the ownership of ideas and is big enough to be publicly available and accessible to everyone. It’s really weird, man, but it is the way of the future. Artists can finally create their own scarce assets and give actual ownership to them.

PG: One of the things you hear a lot about today is the commodification of music. That the rise of things like Spotify over physical media in some ways diminishes the importance our society gives to music. Do you feel like NFTs, because you can own them compared to just a subscription to a streaming platform, can in some way end the commodification of music?

GS: I don’t think it will. I think as technology continues to advance, it will become even easier to get music than it is now. And more and more music will not be assigned a price. I think, eventually, royalties will go away. Services like Spotify will make money by charging artists to have music on their platform. We are already close to that. There are tons of companies out there that charge musicians for placement on certain playlists that they curate themselves on Spotify. This is a sort of scam artistry. Although those placements result in streams, the model encourages the playlister to pay for streams on their playlist to make the artist think that the playlist is getting results. It’s predatory and takes advantage of artists.

As far as a return to the feelings people had when they would go buy vinyl at a record store, that is an experience that can’t be replicated. We will never go back to having music as a scarce asset. In the digital economy, you can represent scarcity by having an NFT that has the vinyl in a 3D model or something similar that you can own. But an NFT is just a number. It is a pointer to the owner of the asset. An NFT is just a commoditization model, not representative of an actual scarce experience. The only way we can go back to making music a scarce asset is to make it artificially scarce, meaning you release it as a .wav file to the person who buys the NFT and somehow convince them to not just do a copy recording of it and sell it or otherwise put it up on the internet. Overall, NFTs are in a completely different landscape than going to a record store and buying vinyl. The nature of the game has completely changed and we will never go back to how music was distributed before.

Part of that also has to do with how diluted music is right now. It is so easy to create and release music today. Even the question of whether something is original music is increasingly an open question. If someone were to simply put together a bunch of GarageBand loops, are they creating an original song? I would argue no, but some people would say yes. It’s ultimately questionable, just as it was questionable when synthesizers first came out and people would use patches to make their music.

PG: And, at least for now, NFTs can also be used to support physical media. Last summer Ropeadope used NFTs to individually number copies of the 20th anniversary vinyl of The Philadelphia Experiment (Ropeadope, 2001). Essentially it used the technology to verify the legitimacy of a physical copy.

GS: Right. To some extent, there is a difference between the real functional use of NFT technology, like with The Philadelphia Experiment re-release, and the more theoretical aspect that we discussed earlier. The functional aspect is just being able to point to something in the real world and say that the NFT is representative of that physical item.

PG: Going back to The Chicago Experiment, how did you select the musicians you were going to work with? It is a rather impressive group.

GS: Well, Makaya [McCraven] and I have had a long musical relationship. We met when I was around 21 years old. Soon after I returned to Chicago from college at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Makaya and I met at a party at Tim Green’s house and hit it off. We were about to play together for the first time as part of a jam session and Makaya told me before we began that he likes to play a little loud. I knew that we were going to be friends for a long time at that moment.

And from there, we did so many projects from scrapping these gigs at a club called Close Up 2, where we did some of our first recordings and duets where we explored Ableton. Actually, I gave Makaya his first copy of Ableton. But even before Ableton, Makaya was chopping up stuff in Logic and using it for our group called the Resonance Quartet. But, yeah, Makaya and I have collaborated on several projects over the years.

And once I got Makaya on board for the project, I started thinking about other Chicago cats that I wanted in on the project. I called a bunch of people and solidified the recording dates. I knew I wanted Marquis [Hill] because his sound is so indicative of where Chicago is now. His sound is very thoughtful, sensitive, and beautifully melodic. And then I asked Jeff [Parker] and Darryl [Jones] to join. I knew I needed to have both of them on it. They’re total legends in their own right.

Joel [Ross] was overdubbed in. We were practicing for a gig I had with Makaya with the vibes up at Makaya’s house and I asked Joel to add to it. And I also knew we needed sax and Irving Pierce was here in LA at the time. I asked him to come into my studio, Tiny Room Studios, to record some parts. And that became the band.

PG: Darryl is in his 60s and Jeff in his 50s while, on the other end of the spectrum, Joel is in his 20s. Was the intent all along to have a multi-generational band or did that just come about from the musicians you chose?

GS: I didn’t specifically set out to make this a multi-generational project. That is more a byproduct of the people I thought would be cool for it. But the fact it is multi-generational is very representative of Chicago itself.

Back in my early 20s, I was checking out jam sessions in the city and started going to The New Apartment Lounge, where Von Freeman was playing and mentoring all these kids. I got to know Von. He was such an incredible mentor to the younger generation of musicians. He saw mentorship as an important part of the community. And that mindset rubbed off on so many other musicians. I mean, even for me, I remember a specific moment where I finished playing at one of Von’s jam sessions. I got off of the stage and Von walked up to me and grabbed my right hand with both of his and starts to rub it. There was this energy from him. It was incredible and he just told me that I shouldn’t let anybody in on my sound. In other words, I should keep true to my sound. Keep refining it and don’t try to be like anyone else. It was in Von’s blood to encourage younger artists and help people find and develop their gifts.

And I felt the same thing with Robert Irving III, who was my first mentor on the piano after my father. When I was 19, Bobby took me under his wing and introduced me to everyone in Chicago. He was one of the reasons I was able to get my feet on the ground there. And that emphasis on mentorship continues today. Makaya has become a mentor to many people. He even picked up Joel in his band before Joel had found his footing and was just up and coming. It’s an important communal fabric that is very special and unique to Chicago and I wanted that represented on the album. So, of course, the album is multi-generational; that’s how our city’s music scene is.

PG: It is great to hear about Robert Irving III. To a large degree, it seems like he has not been given the attention over the years that he deserves. For instance, too many critics far too frequently write off what he did with Miles [Davis] in the 1980s.

GS: I agree. The thing is that too many people – critics, teachers, players, and listeners- tend to stick with what is most familiar to them. And so, with Miles, people often get caught up in the era of his music that they grew up with or spent their most time with. But you can’t discount anything Miles did. He was a genius and in touch with culture in a way very few are. And as for Bobby, he is a creator. He’s a builder. Bobby was an integral part of Miles’ musical landscape in the 80s. But, at the same time, Bobby has never been in it for the notoriety or caring much about what people may say. He doesn’t care about the critics; he just cares about creating more music and mentoring others. I have so much respect for people like that. And, usually, those kinds of people don’t get in the spotlight as much as others.

PG: To bring in another pianist who worked with Miles, how much of an influence has Chicagoan Herbie Hancock been on you? “Rose Petal” sounds reminiscent of 70s Headhunters.

GS: Herbie is an influence on me in so many ways. I met him when I was 23 years old. He introduced me to Nichiren Daishonin’s Buddhism. He eventually took me under his wing and completely changed my outlook on not only music but life in general. Life and music became so much more interconnected to me after spending time with Herbie. He’s been an integral part of my life and developing who I am today. And, of course, we also share a love of music and technology.

“Rose Petal” is definitely a nod to Herbie. While some of the songs on the album are very composed, most of them came together from the band jamming together on mostly improvised performances. I picked out the pieces of improvisation that I liked, chopped them up, and edited them into songs. “Rose Petal” was one of these more improvised pieces. We were just having fun at the time and I allowed myself to slip in my reminiscence of that era of Herbie’s playing, which I love so much. And, so, when I went into post-production, I decided to lean a little more into those influences and added synthesizers.

When it came time to name the piece, I wanted to give it a name that would be a subtle nod to Herbie. So, I originally named it “Chamomile” as in “Chameleon.” But I thought that was a little too on the nose so started thinking about other types of tea. And while I don’t really like chamomile tea, I do love Rose petal tea, so named the song “Rose Petal.”

PG: You mentioned that many of the songs are based on improvised sections. Of course, Chicago is also known for playing a central role in avant-garde improvisational music with things like the AACM and the Art Ensemble of Chicago. Do you feel like those influences came into the recording at all?

GS: Absolutely. I mean, the track “For Too” has many elements of free jazz in it. It’s a composed piece but the composition of the chords and the melody we were playing around those chords came about in a very different and abstract way. It’s not in time. The harmony is often stretched. It brings elements that draw from a certain flavor of the avant-garde.

“Maxwell Street” also draws from a flavor of the avant-garde. I used to play with some of the AACM cats and older cats who really dug into free jazz. Some even played with Ornette Coleman. We would do gigs at the Velvet Lounge and get into these cycles of a groove. We would use a beat of some sort that would cycle and build upon itself. The songs would be harmonically twisted and not use the traditional idea of harmony. But they still retained a harmonic clarity. You could tell what the song was, but couldn’t quite pinpoint it. When I was doing post-production work on “Maxwell Street”, I took elements of the song and looped them around in a way that I think is reminiscent of my time at the Velvet Lounge. Basically, working with a free mentality but from a digital lens.

PG: And “Straight Shooter” seems to recall the electric blues that the city birthed.

GS: “Straight Shooter” just comes from the fact that Jeff is such a bluesy player, man. His sound is just so deep, and you can hear the Blues and roots music in everything he plays. That song came together around Jeff’s performance because it was so gritty but also melodic. It has a deep intuitive melodic sense. There is a brilliant simplicity that happens when you strip away all the unnecessary extra stuff. Jeff does that so well.

PG: One final question – how do you think The Chicago Experiment fits with the three Experiment albums that preceded it?

GS: I see the album as a sort of progression from The Philadelphia Experiment. The other Experiment albums – Detroit and Harlem – are great, in their own right. But if you listen to Philadelphia and Chicago back-to-back, even the beginning moments of both albums are similar. Also, with The Philadelphia Experiment, even though Christian [McBride] was very early in his career at the time, you could see the future of music from the city. I feel like twenty years from now if you visit The Chicago Experiment, you will also be able to see the roots of what has made the music of Chicago so great.

The Chicago Experiment will be available on January 28, 2022, on Ropeadope Records. It can be purchased on Bandcamp.

More information on Greg Spero can be found on his website.

Leave a Reply