|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

One could cogently argue that Bill Laswell is the epitome of an artist unconfined by genre norms. As critic Chris Brazier correctly noted, “Laswell’s pet concept is ‘collision music’ .. bringing together musicians from wildly divergent but complementary spheres and seeing what comes out.” The output of Laswell’s first major band, Material, runs the gamut from dance music to hip hop to jazz to spoken word readings. Another group, Praxis, explores the spaces between rock, metal, and funk. The BBC described another ensemble, Massacre, as “an unholy union of The Shadows, Captain Beefheart, Derek Bailey, and Funkadelic.” Even the nominally free-jazz outfit, Last Exit, with Peter Brötzmann, Ronald Shannon Jackson, and Sonny Sharrock, also had hues of punk music. There is a reason Laswell has become known across the music industry as someone who can develop a new sound. When Herbie Hancock was looking to go in a different direction, Tony Williams referred the pianist to Laswell, resulting in “Rockit”, the jazz/hip-hop/electro hybrid which still stands as a highlight in Hancock’s illustrious career. Miles Davis, ever the musical chameleon, once also sought Laswell’s counsel. Laswell has also produced albums by artists as wide-ranging as Afrika Bambaataa, Laurie Anderson, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Yoko Ono, Iggy Pop, and Henry Threadgill. And that is all just scratching the surface of Laswell’s career. The latest in this long line of eclectic music is Nammu (Ropeadope, 2022), his collaboration with bassist Ulf Ivarsson.

While not as well-known outside of his native Sweden, Ivarsson is no less inventive than Laswell. The parallels between the two are uncanny. One could even argue the two bassists are kindred spirits musically. They both found themselves drawn to their instrument of choice as a teenager. Both cite many of the same influences from across the musical spectrum. They are drawn equally to performance and production. But, perhaps most importantly, is their shared board view of music. Ivarsson’s band Beatundercontrol blurs dub, jazz, funk, electronica, roots, and rock music. Another, Domherrarna, fuses jazz, punk, art-rock, Swedish prog, and noise. A third, Hedningarna, married Scandanavian folk music with electronica and rock.

The idea to pair Ivarsson and Laswell pays off well. The meeting of these two sonic navigators produces a recording that is unique while remaining cohesive. Across its four tracks, Nammu evolves, respectful of the origins of its influences without feeling restricted by them. For instance, “Kishar” begins with the sound of Delta Blues before morphing to electronic music, firey avant-garde free blowing, and then finally settling upon a soft ambient aesthetic. All guided by a deep undercurrent of dub. These changes in approach never seem forced or disjointed. The pieces are unpredictable yet seem to flow organically. It is only in retrospect that a listener will try to identify the roots of different parts. It is that rare type of recording that rewards increased listening.

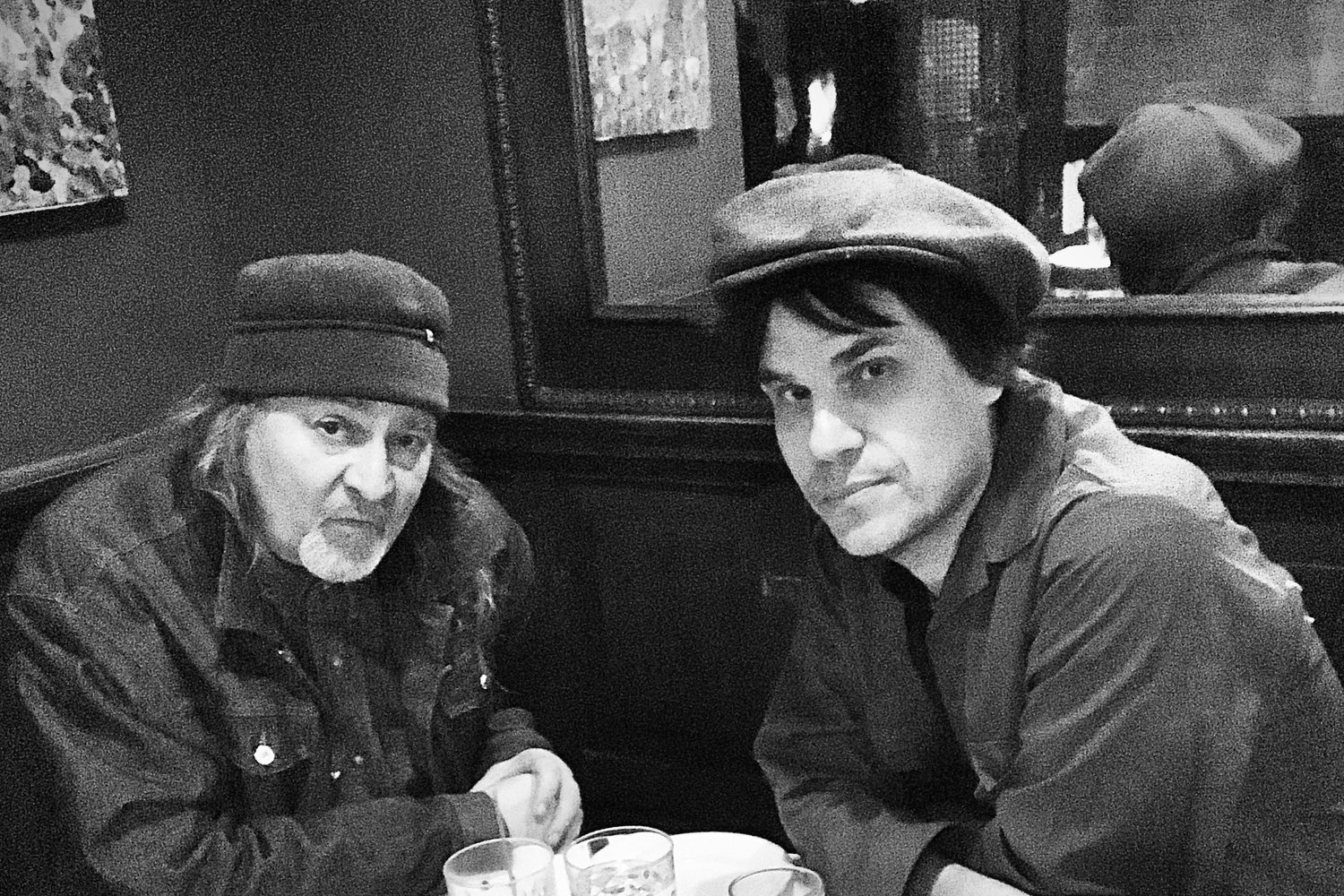

We sat down with Ivarsson and Laswell to discuss the project, their influences, and some of their other projects.

PostGenre: How did Nammu come together?

Ulf Ivarsson: in a way, it started for me in the early 1980s. Musically, I mostly focused on punk at the time. One of my friends was another bassist in my home city, and he gave me a copy of Temporary Music Volumes 1 and 2 (Celluloid, 1981) from Bill’s band, Material. I thought the album was pretty cool and it made me expand my focus a bit musically. It was loose but sounded different from what I heard elsewhere. Not long after, I listened to the Brian Eno and David Byrne record, My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts (Sire, 1981). That whole album, especially the first track, “America Is Waiting” which featured Bill, was great.

Since those two projects, I have always been interested in Bill’s work as a musician, bass player, producer, and composer. I have always enjoyed seeing how he would approach music from different angles, whether it was for a project more in the mainstream musically or something more outside. I have always liked how unpredictable Bill is musically. In many ways, Bill has been a big inspiration to me going way back. I first met Bill around 2007 or 2008.

Bill Laswell: That sounds right.

UI: We had met backstage at one of Bill’s gigs, and I gave him a couple of CDs of my band, Beatundercontrol. The band was working on its third album, In Dub (Malicious Damage, 2010). For the record, I had written four original compositions and was looking for people who could do some remixes on some tracks. I asked Bill if he would mind remixing one of the tracks for us. He agreed and that song, “Secrets of Fascination”, ended up being our first collaboration.

Around 2014 or 2015, I got a little bored playing in so many bands and groups. I started thinking about what would challenge me a bit more musically. That thought process ultimately led me to do several solo performances with just my amplifiers, pedals, loop boxes, and bass. After about four or five performances, I built up some repetitive riffs and decided that maybe I should shift my interest toward recording a new album. Around that time, I contacted Bill to see if he would be interested in coming to Stockholm to do a dual bass concert. I ultimately received some funding from the Swedish Arts Grants Committee to apply towards the collaboration with Bill, but then the pandemic hit and derailed our plans. So, I started thinking about possibly doing a record with Bill instead of a concert. I checked with the Swedish Arts Grants Committee if I could shift my focus toward an album, and they approved.

Once I got the Council’s approval, I started working on putting together arrangements. If you are going to work with someone on the other side of the planet, you need to be very prepared for the project. So, I worked hard putting together as much of the music as possible before I sent it off to Bill. Additionally, to work with someone like Bill, you need to go outside the box and challenge yourself, which requires more work. The general idea was to have most of the orchestration done, send it to Bill with his thoughts, and add any of Bill’s parts. That is how the album came together, and then we worked together with Yoko [Yamabe] to come up with the cover art.

BL: Yoko did a great job with the artwork. She also suggested that the album be connected to Summerian mythology. At the time, I also had done some research on Sumerian religion and culture. Between my research and Yoko’s suggestion, the title fell into place. Yoko’s artwork made the connection complete as it ties so well to the visuals.

PG: Nammu is the Summerian goddess of the sea. Why was that name chosen for the album’s title?

BL: I enjoy using ideas from another culture or territory. It’s great to do something different from the things you hear over and over again. That is one thing I liked about some of Miles Davis’ so-called electric period beyond the music itself. The songs often used titles from different mythologies, and I felt like the Summerian connection was a good one to use on this album.

UI: I very much deferred to Bill in coming up with a title for the album. I knew he would do a good job on song and album titles and working with Yoko for the cover art. It went very well.

PG: And Bill, what interested you in being a part of this project?

BL: I hear certain things in Ulf’s compositions and performances that relate strongly to my ideas. I am drawn to circumstances where I can work with people who take a broad view of music as I do. Ulf definitely meets that standard. I’m often looking for projects like this where there is something in the music that I can relate to.

PG: It is interesting how many similarities there are between the two of you. But you also come from very different places, as Bill grew up in the Midwestern United States and Ulf in Sweden. Do you feel that your different backgrounds give you different perspectives on music despite your similar interests?

BL: I don’t think so. If you lose the geographical distance and concentrate only on music, there seems to be a natural connection between us. We both listen to a lot of the same things. I am older than Ulf, but we have a lot of shared interests musically. I don’t think it matters where we came from because we approach music in a very similar way. That similarity in how we approach music matters far more than where we are from, and I think you can hear that in the album.

PG: One of those connections seems to be a shared interest in combining more ancient musical forms with modern ones. Ulf was in the band Hedningarna, which married old Scandinavian folk music with rock and electronic music. Somewhat similarly, Bill’s Tabla Beat Science mixed Hindustani music, ambient, electronica, drum and bass, and Asian Underground. And Bill also produced albums by Manu Dibango and Fela Kuti, which combined traditional music – Cameroonian and Nigerian, respectively – with more contemporary musical ideas. Do you see much difference between older musical ideas and newer ones?

UI: It’s all music. It doesn’t matter what culture it is or whether the music is a thousand years old, a hundred years old, or brand new. All music should be easy to connect with other music if you listen to it correctly. Purists and musicologists may disagree, but they often don’t make music themselves. They often don’t see music at its most elemental level. I have learned so much about different types of music, from around the world and across different eras, from other artists. That’s true whether it’s Bill, Ginger Baker, or Jimi Hendrix. As long as the music feels natural, it shouldn’t matter where or when it started. What do you think, Bill?

BL: Well, I don’t look for the difference in things. You mentioned Tabla Beat Science a little earlier. Honestly, that band could have been a country-western group, and our overall approach to music would not have changed drastically. With that group, we just played what we felt. We didn’t think about it too much. What matters most is that you go into music with an open mind and see where the music leads you. As Ulf said, you should go with what feels natural and stay away from things that feel unnatural musically. I haven’t had that many experiences where things were not natural, but when it has happened, it’s always been kind of obvious. You just have to listen and think about the overall sound of things.

PG: In a prior interview, Bill noted that “bass parts are everywhere culturally.” Do either of you feel the bass, in particular, gives you more ample opportunity to explore things musically than if you played a different instrument?

UI: It’s really hard to say. Honestly, to get much out of music, I feel like there needs to be a little bit of a struggle. I always like to challenge myself and not stay in areas where I am too comfortable. I can, and have, played rock or pop music. But those types of music are often not very challenging to me, and I tend to get bored. I would much rather be pushed than have something come easily.

Of course, the perfect bass part can set the color of the whole musical picture. So much of that comes from dub. You can see dub in every kind of music. If you listen to Miles Davis with Michael Henderson, it’s the dub that holds that group together.

BL: I agree.

PG: To elaborate a little further on Ulf’s comment, you have both suggested in other interviews that dub is built into every kind of music. Why do you think that is?

BL: Well, someone has to transport it into other music. Otherwise, you wouldn’t make that connection. You have to look at different musical references. But I can say that everything I do has a little bit of dub element in it. Everything from my earliest recordings to today.

UI: Yeah. One really can find dub everywhere. I mean, even in the records of [German electronic band] Tangerine Dream.

BL: Yeah, sure.

UI: That kind of repetitive bass line can be translated into any music. You can find that sound in music far away from Jamaica. You can find it in European music, for instance. The dub sound is very connected to ambient music as well. Going back to Miles Davis, he also had a lot of ambient influences. I don’t know if he thought about it in those terms, but they were there. Dub can relate to any music, I think. You can even translate it to any instrument you want, as long as you keep that repetitive nature of dub when you perform. It’s ultimately up to the artist how much they want to open up beyond the basic foundation of dub.

PG: So, to select one master of dub, you both have a connection to the music of Robbie Shakespeare. Ulf recorded “Robbie Dub”, a single honoring Robbie. And Bill produced Sly and Robbie’s Language Barrier (Island, 1985) and Rhythm Killers (Island, 1987). Do you feel you can sense Robbie’s influence on Nammu?

BL: Well, Robbie is always in everything I do. Even with something fully improvised, there’s always going to be a little Robbie Shakespeare in it. He was also a friend, and I worked with him and Sly [Dunbar] a great deal. Robbie had his own approach and was surprisingly versatile. I find that aspect coming out in my music all the time. I also did a tribute to Robbie with Sly and it comes out as if Robbie was there.

UI: Robbie has been an influence of mine for a long time. When I was a teenager, I played with a reggae band in my hometown. The band’s singer gave me a lot of music, including albums by Sly and Robbie. The first album I heard with Robbie was Black Uhuru’s Red (Island, 1981). I listened to that album a lot. Then I started discovering his bass playing through his albums with Grace Jones. At that point, Robbie had started working with some bigger-name artists. I mean, Sly and Robbie even worked with you on that Mick Jagger album [She’s the Boss (Columbia, 1985))], right Bill?

BL: That’s right. They were both on that album.

UI: Sly and Robbie could play a very broad range and put their color into anything they did musically. Robbie, as a player, was different from many other dub and reggae bassists. That’s apparent if you start comparing him to someone like Family Man [Anston Barrett]. Family Man was very melodic, while Robbie’s approach was much more basic. Robbie had an attitude that less is more. All the great music that Sly and Robbie did, whether with Bob Dylan or Culture, had its own trademark. Robbie was a fantastic musician, and I’m sure his music enters into my approach to composing and performance.

PG: Robbie is far from the only great bassist who has worked with Bill. Bootsy [Collins] and Jah Wobble are two others that come to mind, among several. Bill, how do you feel your experiences with Robbie, Bootsy, or Jah are similar or different from working with Ulf on Nammu?

BL: You know, I don’t see that there should be a huge difference. In all of those cases, everyone is contributing a sound – and, in some cases, lines and things- to the music.

As far as Bootsy, obviously, he plays very differently than Robbie. Actually, I worked a lot with Bootsy and Robbie together. In many of those cases, it was with Bootsy on guitar instead of bass.

As for Jah, I have been working with him since the 1980s. Jah was influenced by Robbie but went out and did his own thing. Like Robbie, Jah is very minimal but went in his own direction.

All four of the bassists you mentioned – Robbie, Bootsy, Jah, and Ulf – are different in their approach and sound, even if there are sometimes some shared commonalities. But the big thing is that they all put everything they have back into the music.

PG: To ask you about another bassist, one of your best production works was Sonny Sharrock’s Ask the Ages (Axiom, 1991). The bassist from that album, Charnett Moffett, passed away fairly recently. Do you have any thoughts on Charnett?

BL: I met Charnett when he was pretty young. When it came time to put together Ask the Ages, Sonny and I were in Berlin. Sonny knew that he wanted to work with Pharoah [Sanders] and Elvin Jones but we were unsure who to put on bass. We initially thought of either Reggie Workman or Charlie Haden. However, I realized at some point that, at least as far as I could tell, Elvin had never recorded with Haden. I didn’t know if maybe there was some problem between Elvin and Charlie, but to make sure there wasn’t one, we put that idea on hold. Ronald Shannon Jackson suggested to us that we pick Charnett to play bass. He felt that Charnett would be perfect because he would listen to Elvin and support the music. And, it was a good idea, so we went with it. I have stayed in touch with Charnett over the years. I last saw him in person a few years ago and was sad to hear of his passing.

PG: Staying with the topic of production, you are both producers in addition to composers and instrumentalists. Do you feel your experience as a producer shapes your skills as a composer or performer?

BL: Well, you know, my performances are mostly improvised. I don’t consider myself a composer really, so it is hard to say.

UI: A lot of people, when they produce music, find that the hardest thing is not seeing the whole picture. Sometimes it can be hard to focus on one instrumental part. I don’t usually have a problem with that, but there is still a lot of learning during the production process. To me, production is always a learning process. Every day is different, and I am always learning.

Click here for Part Two of Our Conversation with Ulf Ivarsson and Bill Laswell. We continue to discuss Nammu, Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, turntables, and the concept of genre.

Nammu will be available on Ropeadope Records on May 27, 2022. It can be purchased on Bandcamp.

More Information on Bill Laswell can be found on his website. More Information on Ulf Ivarsson can be found on his Facebook Page.

Leave a Reply