A History of the Newport Jazz Festival – Chapter IV: Revival, 1961-1964

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Following the riots of the prior summer, there was no Newport Jazz Festival in 1961. However, the city had not abandoned the idea of being a cultural center for jazz. Instead, promoter Sid Bernstein hosted “Music at Newport.” In some ways, it emulated the original. It was set in both the same venue and time of year. It also featured many of the same artists who appeared there throughout the years. That is not to say the two festivals were indistinguishable. Dancers Carmen Delavallade, Norma Miller, and Al Minns each separately performed. Vocalists Bill Henderson, Miriam Makeba, Judy Garland, and the group Lambert, Hendricks & Ross also appeared. So did crowd-pleaser Bob Hope. Yet Music at Newport lacked the magic of the Newport Jazz Festival. Bernstein himself even realized this, noting in an interview towards the end of his event that “the only person who really knows how to handle what goes on up [in Newport] is George Wein.”*

After Music at Newport’s demise, Wein began work resuscitating his festival for the summer of 1962. He trademarked the name “Newport Jazz Festival”, created a new for-profit venture – Festival Productions Inc.- and secured Freebody Park as a site. Newport ‘62, was cut back down to three days in length. However, it did not abandon its broad view of music. Adopting a subtitle: “The Meaning of Jazz” the Festival purposely left open to debate the contours of the term, something made even less definable by its programming choices for the event which emphasized the removal of barriers between people.

Notably, this included making amends with former rebel Charles Mingus who would appear with his sextet. The Festival even attempted to ease growing divides between the East and West during the height of the Cold War with the inclusion of a set titled “Iron Curtain Jazz” by Polish band the Wreckers and its leader pianist Andrzej Trzaskowski.

Perhaps reflecting on the jam sessions that were a highlight of the inaugural festival in 1954, there were also numerous collaborations. Thelonious Monk was a special guest with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Dave Brubeck’s Quartet was joined by Carmen McRae and Gerry Mulligan. Mulligan’s group would similarly feature Bob Brookmeyer and Coleman Hawkins.

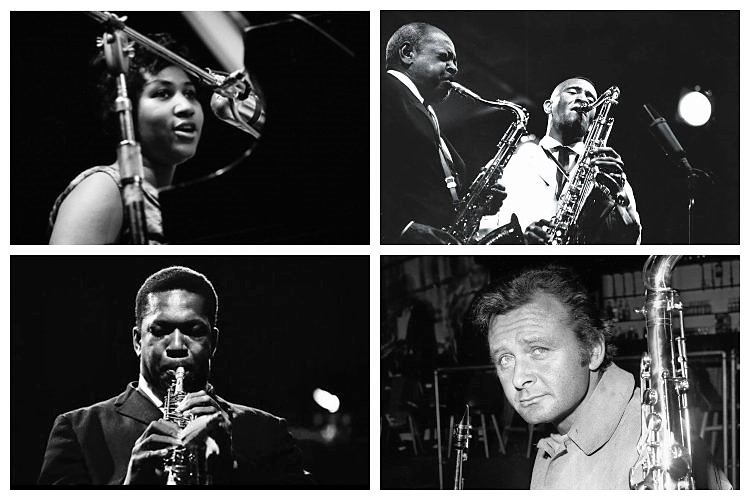

Symbolically reflective of the attempts to minimize divides, Sonny Rollins shared the stage with Jim Hall, Bob Cranshaw, and Ben Riley in promotion of The Bridge (RCA Victor, 1962). Gospel also returned to Freebody by way of the Clara Ward Singers. And a young future “Queen of Soul” Aretha Franklin wowed the audience.

There were also panel discussions on the economics of jazz and the connection between jazz and tap dance. The latter not only attempted to remove a division between the two art forms but had a unique historical significance; tap dance was once presented in the theater that formerly occupied Freebody Park.

The Newport Jazz Festival’s return was an immense artistic success and justified the 1963 edition returning to its full four-day format. That summer’s Festival continued the approach of creating unique musical partnerships. It forged a superpowered House Band consisting of Clark Terry and Howard McGhee on trumpet, Coleman Hawkins and Zoot Sims on tenor sax, Roy Haynes on drums, Gildo Mahones on piano, and Wendell Marshall on bass. Sims and Charlie Mariano joined the Stan Kenton Orchestra. Milt Jackson teamed up with the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet. Clark Terry and Mariano explored the blues with McCoy Tyner, later released as Live at Newport (Impulse! 1964). Pee Wee Russell sat in with both Thelonious Monk’s Quartet and George Wein’s Newport All-Stars. Sonny Stitt visited Maynard Ferguson’s Orchestra. Duke Ellington’s Orchestra met tap dancers Baby Laurence and Bunny Briggs.

But the most memorable was when Sonny Rollins invited his hero, Coleman Hawkins, to join his group. Hawk started his career in a swing style through the 1920s and 1930s. By contrast, Rollins’ Quartet with Paul Bley, Henry Grimes, and drummer Roy McCurdy, was leaning towards a more freely expressive “new thing.” In the abstract, their meeting ran the risk of disaster due to their differences. In reality, they found common ground in a way only two artistic geniuses could.

The 1963 Festival also showcased the Herbie Mann Sextet’s merging of jazz and world music in what would later be released as Herbie Mann Live at Newport (Atlantic, 1963). And then there was John Coltrane in his debut Newport performance. The saxophonist, originally scheduled to perform at the 1960 Festival, was one of the artists whose sets was canceled following the riot.** Three years later, his music was well beyond that which he originally intended to present. With Roy Haynes filling in for Elvin Jones, the quartet made it clear through the leader’s “sheets of sound” that the future of music was stretching outward. It became Newport ‘63 (Impulse! 1963).

The 1964 Festival started with a program titled “Great Moments in Jazz.” The concept was to assemble important musicians who didn’t receive the recognition they otherwise earned including Bobby Haggart, George Brunis, Bud Freeman, Jo Jones, Slam Stewart, and “Wingy” Manone. The following afternoon took the opposite approach by emphasizing new names and faces to the music: Dick Meldonian, Rod Levitt, Ethel Ennis, organist Lou Bennett, and two others. The first was Freddie Hubbard, a year before the legendary Night of the Cookers (Blue Note, 1965). The second was composer and pianist George Russell who five years later would release the groundbreaking Electric Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature (Flying Dutchman, 1969).

The evening of Friday, July 3 emphasized the Festival’s continued artistic expansion as it included Mose Allison who straddled jazz and blues. Sister Rosetta Tharpe did the same with gospel, jazz, blues, and rhythm and blues. But the real coup was the booking of Stan Getz four months after Getz/Gilberto (Verve, 1964) skyrocketed in popularity and created a Bossa Nova craze. Despite the success of the album – it still ranks on many best-of lists – there was animosity between the saxophonist and vocalist Astrud Gilberto. Despite this, Wein was able to convince them to perform their classic “Girl from Ipanema” together. Chet Baker would also join.

The highlight of July 4th was the Max Roach Quartet’s presentation of The Freedom Now Suite with Abbey Lincoln. Although originally recorded in 1960, its performance at Newport came at a perfect time. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing racial segregation in schools, public accommodations, and employment, became law only a week before that year’s Festival. While full equality was still unachieved, the law promised a brighter future.

But the success of the Newport Jazz Festival from 1962 to 1964 also meant large and more unruly crowds visiting the city. Some residents, including members of the city council, became increasingly concerned about the prospects of another riot. Early on the morning of July 5th, a few hundred young visitors to Newport lit a bonfire on Second Beach. The city council responded by enacting a new rule prohibiting festivals from taking place at Freebody Park following that day’s scheduled performances including a headlining performance by Sarah Vaughn. Although Sassy had sung at prior years’ festivals, it marked the first time she received the full recognition she deserved. From her uptempo “Like Someone in Love” to her sentimental version of “Misty” she cemented her standing among the best vocalists. Backed by the Bob James Trio, it also hinted at smoother fusion sounds which would emerge in the next decade. It was also a beautiful way for the Festival to say goodbye to its home.

In some ways, the need to find a new venue was unsurprising. The Festival had been outgrowing Freebody Park for several years. Seeking a more long term answer, Festival Productions looked to a thirty-five-acre open field owned by a commercial fishing company. The land was littered with nets and the stench of dead fish. And yet, it had promise.

The 1963 Newport House Band’s “Chasin’ at Newport” can be heard on-demand as part of WBGO’s Jazz Night in America with Christian McBride.

Jazz Night in America will also be broadcasting the House Band’s version of “Indiana” and Sarah Vaughn’s performance from 1964 will be available on WBGO on July 31 at 11PM EST and again on August 1 at 6 PM EST.

It is also available on-demand.

Freddie Hubbard’s 1964 set is available on the Newport Jazz Festival’s website.

Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln’s 1964 performance is also available from the Newport Jazz Festival.

Significant portions of this chapter were adapted from George Wein’s autobiography (written with Nate Chinen) ‘Myself Among Others’ (Da Capo Press, 2004) and ‘50: The Newport Jazz Festival, 1954-2004’.

* Things would turn around for Bernstein; he would later become known as “The Father of the British Invasion” due to his role in bringing the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, the Dave Clark Five, the Moody Blues, and the Animals to America for the first time.

** However, Coltrane did appear in Newport in 1961 as part of Bernstein’s Music at Newport. He was with McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones, and two bassists- Reggie Workman and Art Davis.

2 thoughts on “A History of the Newport Jazz Festival – Chapter IV: Revival, 1961-1964”